|

|

|

|

|

Record Reviews 4:

In Greenwich Village -

The Last Album

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Greenwich Village

The Village Concerts

Live in Greenwich Village: The Complete Impulse Recordings

Love Cry

New Grass

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe

The Last Album

In Greenwich Village

Down Beat (Vol. 35, No. 14, 11 July, 1968- p.26) - USA

Albert Ayler

ALBERT AYLER IN GREENWICH VILLAGE—Impulse 9155: For John Coltrane; Change Has Come; Truth Is Marching In; Our Prayer.

Personnel: Ayler, alto saxophone; Joel Friedman, cello; Alan Silva, Bill Folwell, basses; Beaver Harris, drums (tracks 1-2). Ayler, tenor saxophone; Donald Ayler, trumpet; Michel Sampson, violin; Folwell, Henry Grimes, basses; Harris, drums (tracks 3-4).

Rating: * * * * *

The element of “play” seems to me a crucial component, perhaps the crucial component, of the new jazz. Let me clarify this. By play I don’t mean something insignificant, without seriousness or meaning, but rather that rational irrationality which is one of man’s highest activities. It is such play that produces works of art, and which in fact may be the very essence of man’s artistic impulses.

The importance of play in culture has been recognized by a number of thinkers, and more than one has put his mind to an investigation of the matter in an attempt to arrive at a knowledge of the essential nature and characteristics of play (in this respect, I can recommend the book Homo Ludens by the historian Johan Huizinga). Huizinga describes play as “. . . a free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious’, but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. . . . It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner.”

The play spirit prompts all artistic works, for it is play which lies at the very core of all metaphorical, symbolic, representative, and imaginative actualizations, displays, and performances. The real affinity between play and music, for example, is vividly revealed in our very term for describing the manipulation of a musical instrument: one “plays” an instrument, and the instrumentalist is a “player.”

In its emphasis upon improvisation—unplanned spontaneous composition or recomposition—jazz offers a particularly vivid, immediately observable manifestation of the play element. And avant-garde jazz—with its insistence on totally interactive, extemporized music-making—seems to represent perhaps the fullest actualization of the play spirit in jazz since early New Orleans music burst upon an amazed world more than five decades ago.

All this is prompted by this Ayler record (the best I’ve heard); to my way of thinking, the music of the various groups Ayler has spearheaded has represented some of the most perfect realizations of the artistic goals of the avant garde. (I may not have liked all the music they have produced, for the goals and the end-products are two entirely different things, after all.) In this, Ayler’s music has represented the fullest realization of the play principle as well. Totally improvised music would have to, wouldn’t it? And that’s what Ayler has always striven for in his music—a total spontaneity of group utterance, “absorbing the player intensely and utterly” and at the same time proceeding “within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner.” Ayler’s music goes this one better, for it fixes those boundaries and sets those rules in the very heat of play itself.

In a very real sense, then, Ayler and his confreres are creating their own ordered cosmos in their music, as they make that music. And this album offers the best, fullest, most perfect view of that musical cosmos I’ve heard so far. Two different ensembles are heard here (Truth Is Marching In and Our Prayer were recorded at the Village Vanguard Dec. 18, 1966; the other two pieces were taped at the Village Theater two months later), but both create basically the same world of sound and images.

It’s difficult to describe that world, but the textures the two ensembles create do seem like a fusion of early jazz and mariachi music, the resemblance to the latter being more pronounced on the two tracks featuring the group with trumpeter Donald Ayler. The music is vividly alive, churning, full of colors and textures, and relentlessly moving. There is a great deal of energy and restless passion to it, yet it doesn’t sound “disturbed” or otherwise disoriented. Ayler’s music is not at all incomprehensible or difficult of access. All it requires is a pair of open ears, a willingness to enter a world of musical thought that might on the surface seem alien and uncomfortable. It’s not, though. The vistas are fresh, the natives friendly and, as the ad says, “getting there is half the fun.” There’s a lot of the latter in Ayler’s music.

This album is worth your attention, believe me. Ayler may well be the Johnny Dodds of the avant garde, and in my book that’s high praise, perhaps the highest.

—Welding

(Pete Welding)

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 162, January 1969, p.38) - France

albert ayler

In Greenwich Village : For John Coltrane / Change has come (2) / Truth is marching in / Our Prayer (1).

1 Albert Ayler (ts), Donald Ayler (tp), Michael Sampson (vln), Bill Folwell, Henry Grimes (b), Beaver Harris (dm). Village Vanguard, New York, 18 décembre 1966.

2 Ayler (as), Joel Friedman (cello), Alan Silva, Folwell (b), Harris (dm), New York, 26 février 1967. Impulse 9155 / 33 t / 30 cm.

9/10 Domaine par excellence l’instable, pôle d’affolement de toutes boussoles, lieu du plus grand écart et contraste entre phases «sauvages» (les explosions et tourbillons sonores, le bouillonnement d’un bru(i)t indéchiffrable, au-delà des codes) et phases «culturelles» (rengaines, ritournelles, scies, marches et autres musiques de manège surconnotées), la musique d’Ayler, une fois acquis ce principe de fonctionnement, fixé ce système de désarticulation maximale du champ musical en deux plans antagonistes, l’un hyper-référentiel, l’autre a-référentiel, semblait prise à son propre piège, contrainte au sur-place, à un statisme consécutif à son extrême bipolarité. Ecartelée entre deux mo(n)des inconciliables — et par là condamnée à ne se développer que par variations et diversifications à faible amplitude de ce système, lui immuable, d’aller-retour. A moins que, accomplissant ce qu’il faut bien nommer une sorte de mutation, elle ne renonce à son principe exclusivement binaire, et, soit privilégiant l’un de ses deux bords, soit dialectisant leur opposition par le recours à un troisième mode, elle n’en vienne à son tour à évoluer culturellement.

C’est en tout cas ce dont semblent témoigner, bien que peu récents (décembre 66 et février 67), les enregistrements groupés dans cet album. L’on y constate toujours à l’œuvre le même effet de rupture, la même solution de continuité entre la part des rengaines, fanfares, hymnes, lyrismes grotesques, et celle des délires, balbutiements, cris, rages; mais entre elles, un facteur intermédiaire (et relativement nouveau, bien que timidement apparu dans les auto-citations de la suite des «Ghosts») s’est développé au point de tenir désormais le principal rôle: l’utilisation musicale intensive d’une part des références culturelles du free-jazz, d’autre part de ce qui, dans le free-jazz (et la propre musique d’Ayler), est devenu référence et culture. Il n’y a plus une bipartition radicale du champ musical en d’un côté une zone «primitive», élémentaire, foyer des premiers souvenirs, des remembrances, des initiations, et une zone de la violence créative, avec entre elles un vide, le refus de ce que fut le jazz; ce «vide» est en train de se combler: entre l’origine et l’aboutissement prend place la seule évolution culturelle musicale qu’Ayler ne rejette pas (puisqu’il en est l’un des auteurs): la free-music elle-même. Tout se passe comme si l’outlaw Ayler rentrait dans le rang maintenant que s’est constitué, à force de refus et caricatures d’une part, de délires et recherches d’autre part, un entre-deux proprement musical où circuler librement. L’indice majeur de cette liberté nouvellement acquise pour Ayler, c’est ici l’utilisation massive des cordes (violons, violoncelles, basses) traitées «à l’européenne», renvoyant explicitement à leur usage dans la musique occidentale contemporaine (comme dans certains enregistrements plus anciens d’Ayler un clavecin surgissait au milieu des bals de campagne). Cela nous vaut, autre mutation, de très belles recherches d’harmonisation, d’accord et de mimétisme entre sonorités des cordes et son du saxophone.

L’autre indice de ce retourde 1’enfant prodigue dans le sein du jazz, c’est bien sûr l’hommage à Coltrane — d’autant plus révélateur qu’Ayler n’a rien d’un héritier de Coltrane, contrairement à presque tous les autres saxophonistes du free. Jouant lors de l’enterrement de Coltrane, Ayler pouvait jeter un pont entre primitivité (la référence aux «enterrements à la Nouvelle-Orléans») et nouveauté (sa propre musique): l’enterrement de John Coltrane est le lieu et le temps synthétique du début et de la fin du jazz.

Point nécessaire donc, pour «comprendre» ce disque, de faire, comme le voudrait Michel Le Bris, «référence à la thématique nietzschéenne», laquelle heureusement résiste très bien à tel détournement de sens (Gilles Deleuze et Frederic Nietzsche répugnant à servir de bouche-trous à la critique de jazz) et continue de trancher surréalistement (comme ce parapluie sur table de dissection), au milieu des chroniques de notre confrère Jazz Hot. Comme dit un commentateur: «L’equipe actuelle de Jazz Hot estime avoir des choses à dire et pense aussi que ces choses seraient difficilement dicibles dans les colones de notre estimé confrère (i.e. Jazzmag).» Ici ou là, de toute façon ces «choses» restent «difficilement dicibles».

— J.-L. C. (Jean-Louis Comolli)

Record Reviews

Discography: In Greenwich Village

*

The Village Concerts

Jazz Hot (May 1978) - France

ALBERT AYLER

Light In Darkness (3). Heavenly Home (3). Spiritual Rebirth (3). Infinite Spirit (3). Omega Is The Alpha (3). Spirits Rejoice (1). Divine Peace Maker (1). Angels (2).

(1) Don Ayler (tp), Albert Ayler (ts), Michel Sampson (vln), Bill Folwell, Henry Grimes (b), Beaver Harris (d).

(2) Albert Ayler (ts), Call Cobbs (p), Bill Folwell, Henry Grimes (b). NYC, The Village Vanguard, 18 décembre 1966.

(3) Don Ayler (tp), Albert Ayler (ts), Michel Sampson (vln), Joel Freedman (cello), Bill Folwell, Alan Silva (b), Beaver Harris (d). NYC, The Village Theatre, 26 février 1967.

Impulse, ABC, AS 9336/2 (Distr. Carrère) (2C).

De la premiere séance nous connaissions Truth Is Marching In et In Our Prayer, de la seconde For John Coltrane et Change Has Come, publiés sur “Albert Ayler In Greenwich ViIlage” (Impulse 9155). Tous les autres titres présentés dans ce “Village Concerts” étaient inédits.

Leur publication nous est donc précieuse. D’abord parce quelle remet en pleine lumière l’oeuvre magique du grand Albert qui a fort rarement l’occasion de figurer dans les chroniques discographiques: la plupart de ce qu’il a enregistré n’est actuellement pas disponible, faute de rééditions. On risque fort ainsi, nouveau venu au jazz, d’ignorer la force, la fantastique prégnance d’une oeuvre qui compte parmi les lieux essentiels de la musique improvisée.

A tous, familiers ou ignorants de la saga aylerienne, ce double disque apportera quelques révélations. En premier lieu sur le plan du rôle historique d’Albert Ayler. Très joliment, ainsi que le rapporte le texte de pochette, Anthony Braxton en définit l’importance. Il le présente comme l’aboutissement d’un langage, nourri de lyrisme et de mysticisme. Langage parvenu à ébullition avec John Coltrane et Pharoah Sanders, amené jusqu’au point d’évaporation par Albert Ayler. Et il est vrai qu’avec ce dernier, par la chaleur du son, par l’apparente simplicité harmonique, par l’insolite couleur orchestrale (contrebasses, violoncelle, violon à côté de trompette et ténor: le choeur des anges derrière la voix divine), par la ferveur lyrique enfin, l’on atteint à la dimension du merveilleux. Un merveilleux où la violence s’évapore en credo, où la ligne mélodique se veut conviviale. Il y eut par la suite bien des pseudo-mysticismes bêlants. Pour Ayler la dévotion ne s’illustre jamais dans la mièvrerie. Et lorsque la forme en appelle autant à la fanfare (Spirits Rejoice) qu’aux cantiques dominicaux, c’est que de toute manière, païenne ou religieuse, cette forme habille la fête. Mais pareille ioie, pareille immensité dans le chant ne devaient plus être jouées. Précisément parce qu’il est impossible de les “jouer” (de les simuler). Albert Ayler est un musicien du premier degré, corps et âme, souffle et motivation complètement impliqué dans sa musique. Tous les morceaux ici restitués le donnent clairement à sentir: Albert Ayler était inspiré.

Sur un plan plus étroitement musical, on a pu décrier la simplicité (?) de sa musique. Certes, ni Light In Darkness, ni Heavenly Home, ni aucune des compositions ici présentes ne jonglent avec des harmonies complexes ou des subtilités rythmiques. Cette musique n’en est pas moins dense et riche. Dense par les discours individuels: celui terriblement fascinant d’Albert, mais aussi celui de son frère le trompettiste Don Ayler. Fortement sous-estimé (parce que défini par sa fraternité), Don Ayler représente pourtant le prototype de discours à la trompette mis en avant par Sun Ra (Michael Ray et Ahmed Abdulah aujourd’hui). Une certaine démesure dans le discours collectif force également le rapprochement avec le Soleil-Soleil de Chicago. Quant à la richesse c’est sur le plan des couleurs orchestrales qu’il faut la trouver. En cette ère des grands souffleurs et des sections rythmiques, il fallait oser présenter, avec deux cuivres et une batterie, un quartette à cordes! Fonctionnant sur l’antique principe des choeurs, les cordes fournissent un soubassement mélodique qui balance entre contrepoint et mélopée. Tantôt la couleur du violon est mise en exergue, tantôt celle des basses ou/et du violoncelle... Ayler présentait alors une formule restée inexplorée.

C’est donc sur ce plan orchestral, comme sur celui des discours individuels (cf. David Murray...) que l’héritage d’Albert Ayler a le plus de chance d’être mis à profit aujourd’hui. Sa démarche, quant à elle, qui constitue la clef de voûte, la raison de vivre de sa musique, a bien été noyée dans l’East River avec lui.

Enfin, Angels nous présente le ténor dialoguant avec un piano que l’on a tendance à attribuer à Call Cobbs, sans certitude aucune. Il s’agit là d’une ballade, parfaitement épurée. Elle possède l’immense majesté du Balzac de Rodin, grave et puissant, dans le brouillard de Sceaux, tel que l’a immortalisé Edward Steichen. Jailli du fin fond d’un torrent intérieur, la musique déborde alors les genres. Le mysticisme n’a plus de dieu, Albert n’est jamais mort. Et son chant n’a pas de fin.

Alex Dutilh

*

The Village Voice (7 August, 1978, p. 43-44) - USA

Albert Ayler as

Angel of History

By Richard Mortifoglio

Since most jazz musicians lack an “image” nowadays, it is fascinating that the late saxophonist Albert Ayler remains contemporary in new rock culture. Ayler himself attempted to be a popular musician by playing nursery-rhyme folk tunes designed to excite instant recognition and universal appeal. Like Levi-Strauss, he embarked on a quixotic anthropological quest for deep structures of the global mind. Titles like “Angels,” “Ghosts,” “Children,” “Mothers,” “Vibrations,” and “Universal Indians” reveal somewhat the abstract nature of his musical program. He was also notorious for a frenetic free blowing, which shocked even spiritual fellow travelers. But his apocalyptic politics also shook them into rethinking their budding black nationalism and private spirituality in more utopian terms, without the usual illusions. For all his rhetoric of peace and joy, Ayler had one of the most agonized sounds in jazz history; not even Ornette approached such eerie desolation. And while Coleman became semi-respectable under the patronage of John Lewis, Ayler more than anyone represented the supposed charlatanry (and real threat) of the “New Thing” to the jazz establishment.

Before and after New Year’s 1967, Ayler introduced a new ensemble consisting of a string quartet of sorts plus Beaver Harris on drums and brother Donald Ayler on trumpet. Previously, the classic Albert Ayler in Greenwich Village was the only document of this happy phase in Ayler’s middle period. Now Impulse has released the remaining performances on its new Dedication Series. Except for the seminal ESP-Disc records, much of Ayler’s work is available, from the frightfully intense Vibrations, his single most powerful session, to the much denigrated pop-rock experiments with Canned Heat guitarist Henry Vestine. But this representative collection proves he was not so outside the jazz tradition as his archaic tone and outer-space aspect implied.

Playing it straighter than ever these nights, Ayler demonstrated his virtuosity in the Rollins style of rigorous thematic development. The culmination of this tendency was the poppish Love Cry, his easiest, most attractive work. But already the change is dramatic, as “Angels” testifies. On Spirits Rejoice, “Angels” is a terrifying shade of Guy Lombardo drunken revery accompanied by the enigmatic Call Cobbs on bony harpsichord. Here Cobbs contributes a rollicking yet elegant whorehouse-piano edition of the same keyboard script while Ayler brightly states his robust theme, ending prettily with a Coltrane tag phrase. On the rest of the pieces the ensemble work created an elegaic interplay of strings and saxophone that sacrificed nothing of the Ayler brothers’ militant statement of their themes.

One reason for Ayler’s recent popularity si that he grew reluctant to rush through his heads. He dwells lovingly on each Mexicali funeral procession, Custer cavalry call, gospel relay, and Quasimodo ding-dong bell, juxtaposing them in a whole-earth collage. He split these quaint atoms apart in explosive short circuits of improvisation buoyantly carried by clouds of strings. More than merely eclectic, Ayler was a self-appointed angel of history, announcing the past’s redemption in planet waves of light-speed communication. However eccentric, he was a genuine American artist in his search for cosmic potential in the homely and ready to hand.

One paradox about Ayler is that he took on advanced technological problems with traditional means. His folkishness aside, he played electric acoustic; vibrato and fuzz-box were built into his blowing technique. He was able to bridge an industrial society and McLuhan’s global network of infinite imagery. When I read his broadsides about flying saucers chasing him and Donald down, I realize he was somewhat insane. But he was able to harness his schizophrenia for coherent social ends; he understood modern chaos better than either Schoenberg or Cage, who more properly represent it. A great moral artist, Ayler, like Rilke, experienced these historical fissures deep enough to resolve them in an art of healing, compensation, and growth.

*

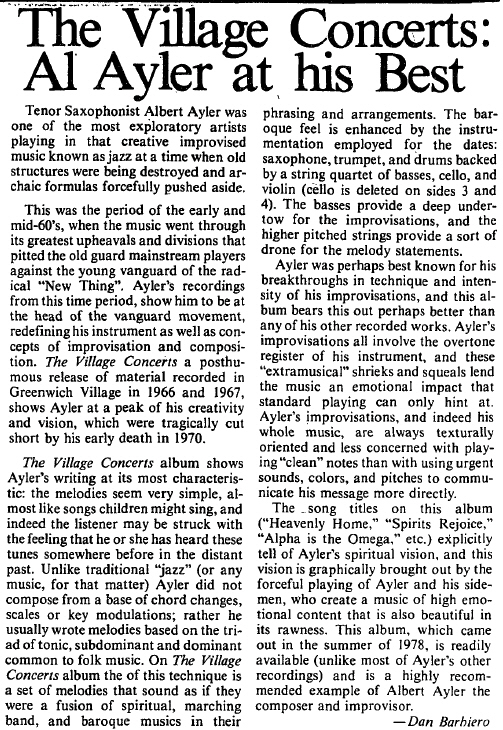

The Hoya (Georgetown University, Washington, 26 January, 1979, p. 8) - USA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Record Reviews

Discography: The Village Concerts

*

Live in Greenwich Village: The Complete Impulse Recordings

Jazz Journal International (May, 1999, p. 21-22) - UK

ALBERT AYLER

LIVE IN GREENWICH VILLAGE

(1) Holy Ghost; (2) Truth Is Marching In; Our Prayer; Spirits Rejoice; Divine Peacemaker; (6) Angels (64.04)—(4) For John Coltrane; (3) Change Has Come; Light In Darkness; Heavenly Home; Spiritual Rebirth; Infinite Spirit; Omega Is The Alpha; (5) Universal Thoughts (70.09)

(1) Ayler (ts, as); Don Ayler (t); Joel Freedman (clo); Lewis Worrell (b); Sunny Murray (d). New York, March 28, 1965

(2) as (1) but Michael Sampson (vn); Bill Folwell (b); Henry Grimes (b) and Beaver Harris (d) replace Freedman, Worrell and Murray. New York, Dcember 18, 1966

(3) as (2) but Freedman (clo) and Alan Silva (b) replace Grimes. New York, February 1967

(4) as (3) but omit Don Ayler and Harris

(5) as (3) plus George Steel (tb)

(6) Ayler (ts); Probably Call Cobbs Jr. (p); Gary Peacock (b). New York, December 18 , 1966

(Impulse IMP 22732)

In a recording career spanning only eight years, Ayler made a major contribution to the evolutionary progress of jazz. This outstanding double CD covers a period of almost two of these years, was recorded on location and takes us from the explosive Holy Ghost of 1965 to an incomplete Universal Thoughts of 1967. That title had never previously been issued but the remainder made up all or part of New Wave In Jazz (AS 90), Ayler In Greenwich Village (AS 9155) and Ayler: The Village Concerts (IA 9336-2).

Live features Ayler at his best. His themes are an incongruous mixture of heartfelt naiveté and open magniloquence, while his solos continually seek to free themselves from thematic or motivic consistency. He frequently moves into the field of aural sensation, subjugating his use of rhetoric, as incantatory violence walks hand in hand with melodic variation. Ayler was a hyper-emotional player and Change, Light and Truth contain examples of his finest work. It is perhaps an over-simplification, however, to think of headlong tirades as the only basis of his style. The pathos in his essentially simple solo on Spirits Rejoice or his realisation of the New Orleans funeral fanfare and dirge on Spirits Rejoice provide evidence of his broader stylistic range. This latter track, in particular, underlines the fact that he had as much in common with the music’s primitives as he did with contemporary saxophonists.

Don Ayler, absent from only two titles, has his best moments on Truth, Spirits Rejoice and Omega and is an ideal foil for his brother. Like Don Cherry, he is suspicious of rounded contours. He attacks with total commitment, matches Albert’s abstract emphasis and employs the same rumbustious rhythmic movements.

Of the support team, Freedman and Sampson play important minor roles. All of the bassists are quality players and the use of two, in the majority of instances, gives the horns an increase in options. Despite Murray’s more oblique rhythmic references, both he and Harris serve the drum stool and the group, as a whole, rather well.

Some time ago, a bunch of JJI contributors debated jazz’s five most important tenors. A minority of three (Ansell, McRae and Tucker) were alone in suggesting Hawkins, Young, Coltrane, Rollins and Ayler (date of birth order). Scant support for this selection was almost entirely due to the inclusion of the last named. This superb album goes a long way toward answering questions regarding his selection and, more significantly, demonstrates why the post-Ayler school is now such a world-wide club.

Barry McRae

*

Coda (No. 285, May/June 1999, p. 28) - Canada

ALBERT AYLER

Live in Greenwich Village:

The Complete Impulse Recordings

Impulse IMPD -2-273

CONTRARY TO WHAT that confusing title might suggest, these are hardly the “complete” Ayler Impulse recordings. Missing are all the studio recordings, both the brilliant quintet of Love Cry and the later “fusions” of Music Is The Healing Force In The Universe and New Grass. What is here is apparently all the Ayler live recordings for Impulse, reuniting the two concerts (from December 18, 1966 and February 26, 1967) previously fragmented on Albert Ayler In Greenwich Village (issued on lp in 1967 and later as a CD with identical content) and Albert Ayler: The Village Concerts (issued as a 2 lp set in 1978). This new 2 CD set also includes the wonderful Holy Ghost a 1965 quintet recording with Sunny Murray and cellist Joel Freedman that was previously available only on the original lp issue — and not on the CD “reissue” — of The New Wave in Jazz (Impulse AS-90), a live sampler of the avant-garde that appeared circa 1966. Added too, is an incomplete recording of Universal Thoughts from the 1967 concert, which adds trombonist George Steele (a name unknown to this reviewer) to the string-rich ensemble that included violinist Michel Sampson, Freedman and bassists Bill Folwell and Alan Silva. Those discographical matters aside, there’s little to do but recommend this extraordinary music, with highlights too numerous to mention, finally issued in an appropriate form. Ayler was both a great saxophonist and musical architect. Here his simplified folk-like melodies combine with his brother Don’s brassy trumpet, Beaver Harris’s free marching-band drumming and the quavering, slashing strings to create a marvelous “global village” band and an inspiring setting for Ayler’s convulsive, often astonishing solos.

Record Reviews

Discography: Live in Greenwich Village: The Complete Impulse Recordings

*

Love Cry

The New York Times (23 June, 1968, p.148) - USA

Jazz: From Passionate Ballads to Avant-Garde

By MARTIN WILLIAMS

. . .

Also disappointing is Love Cry by Albert Ayler (Impulse A-AS-9165). Ayler, a tenor saxophonist much influenced by John Coltrane, has shown himself an interesting improviser on past occasion. He has exceptional control of the upper, “false” reaches of his horn, and he has learned (from Ornette Coleman, I would say) to use a deliberately false, harsh intonation for sustained emotional effect.

Ayler is the sort of musician whose work is for some people at first repellent, but he has demonstrated that he can be a very orderly player, able to state and develop a single idea or motive through a series of improvised, linking permutations. Thus, anyone who believes the jazz avant-garde invites chaos should hear him.

He is probably best introduced by My Name is Albert Ayler (Fantasy 6016, stereo 86016) wherein he works with traditional materials, and by Spiritual Unity (ESP-Disc 1002) wherein he works with four thematically related pieces of his own, all using simple—perhaps simplistic—folklike ideas. As a start, try “The Wizard” on the latter LP. There is a bizarre beauty to it.

On the “Love Cry” album there is also a great deal that is bizarre. I appreciate the interplay between Ayler and his trumpeter brother, Donald, on “Ghosts” and “Bells,” and the honest emotion in Ayler’s high-pitched solo on “Universal Indians” (there are no notes in the new jazz, he once suggested, only pure feeling). But there seems to me to be a strident, staccatoed, vibratoed and perhaps self-conscious sameness to much of this music.

*

Down Beat (Vol. 35, No. 12, 1968, p 28-29) - USA

FOUR MODERNISTS

Archie Shepp

IN EUROPE—Delmark DS 9409: Cisum; Crepuscule With Nellie; O.C.; When Will the Blues Leave; The Funeral; Mik.

Personnel: Don Cherry, cornet; John Tchicai, alto saxophone; Shepp, tenor saxophone; Don Moore, bass; J. C. Moses, drums.

Rating: * * * ½

Pharoah Sanders

TAUHID—Impulse A-9138: Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt; Japan; Aum; Venus; Capricorn Rising.

Personnel: Sanders, tenor saxophone, flute, piccolo; Dave Burrell, piano; Warren (Sonny) Sharrock, guitar; Henry Grimes, bass; Roger Blank, drums; Nat Bettis, percussion.

Rating: * * * *

Cecil Taylor

CONQUISTADOR!—Blue Note BST 84260: Conquistador; With (Exit).

Personnel: Bill Dixon, trumpet; Jimmy Lyons, alto saxophone; Taylor, piano; Henry Grimes, Alan Silva, basses; Andrew Cyrille, drums.

Rating: * * * * *

Albert Ayler

LOVE CRY—Impulse A-9165: Love Cry; Ghosts; Omega; Dancing Flowers; Bells; Love Flower; Zion Hill; Universal Indians.

Personnel: Donald Ay1er, trumpet; Albert Ayler tenor saxophonc; Call Cobbs, harpsichord; Alan Silva, bass; Milford Graves, drums.

Rating: * * * * ½

A lot of people, for a lot of reasons, have nothing good if anything at all to say about the latter-day saints of jazz. At bottom, I believe, most of this criticism and apathy stems from selfish prejudices and fears. From time to time, every art form has faced—and gone past—the objections to its abstract manifestations. Not so jazz.

Over half a century ago, the New York Armory Show broke a path for everything up to and including the absurdities of pop art’s worst protagonists. Kerouac, e.e. cummings and Jean Genet no longer cause traumas, either from the standpoint of style or content. Giacometti, David Smith, and those cats with the neon lights have all been survived. Ionesco, Brecht, and Le . . . yes, even LeRoi Jones have been digested without adding to the number of inmates at Charenton. But when it comes to that “way out music. . . .”

If Andy Warhol has a Dunn&Bradstreet rating, Joseph Jarman should have a listing in Fortune. In this age of superjets, Lamborghinis, and Remington 30-06s; in this era of peace parades and poor marches; in this time of assassination politics and police versus students and napalm versus epidermis, Pennies From Heaven, even taken up- tempo, just doesn’t seem to speak to the moment. Rather, that moment is more faithfully reflected in the febrile community of sounds inadequately lumped together under the heading of avant garde.

No one can say but the artists themselves that their performances are the conscious expressions of these contemporary elements of our existence. But the screams, the bent, twisted, broken, cut and shot tones that leak and explode from their instruments are full of imagery from somewhere, and it’s not merely the hip thing to do to hear them— there is value and reward in listening to these players, just as there was in listening to King Oliver.

Shepp’s album, recorded in Denmark in 1963, is characterized by a blowing approach which seems, in retrospect, almost a conscious rebellion against the bebop influence. The front line remarks, knitted together by a straight-ahead rhythm unit, were somewhat influenced by the Ornette Coleman efforts which preceded this work by several years. Furious phrasing, loosely based on the heads, followed by abrupt stops; hiply out-of-joint bop lines done in haphazard unison, were all in the Coleman genre. But Shepp, Tchicai, Cherry, et al., were the original New York Contemporary Five, and, as such, influenced not only subsequent NYC5s but a legion of instrumentalists from then till tomorrow.

The trumpeter’s piece, Cisum, is an apt launching pad for his high-flying solo here. Tchicai, likewise, grinds exceedingly fine. Moses and Moore pace the group in a correctly unmerciful manner for the more than 11 minutes the track runs. Shepp returns, tit for tat, what the rhythm lays on.

The inclusion of Roswell Rudd’s verbatim scoring of Monk’s Crepuscule was no doubt due to Shepp’s well-founded awareness of and respect for his heritage.

The rambling O.C. theme is quickly followed by solo Shepp, who sets a standard for eventful monologue.

When Will, by Ornette, finds Cherry right at home—except that his phrasing is much tighter and more confident today than it was five years ago. Tchicai, with good delayed-beat comments, a la Ornette, was competent; was one of the only players doing it then; but he too has come a mile or two since. Shepp, with snatches of I Remember You, etc., leads the horns into a melange of group improvisation to emerge alone.

Shepp’s Funeral, dolorous, full of fine abstract sound elements, is graphic in its portrayal of pain, and fits its later purpose: acknowledgment of one of U.S. racism’s many victims, Medger Evers.

Tchicai’s Mik follows the 12-bar structure in common meter. The composer’s solo is relaxed; Cherry’s is original and Shepp’s is unique.

Sadly, this album was recorded so long ago that much of it is no longer as interestingly spontaneous as it once was.

Happily, Delmark’s Bob Koester saw fit to purchase it from its European owners and give it to us even at this date. It provides us with further history of the middle of the past decade’s significant jazz activity. As such, it is valuable source material, as well as good music.

Thanks to the insight (foresight?) of John Coltrane, another first-rank tenor is on the scene. Pharoah Sanders would undoubtedly have been overlooked for many years (if not entirely) as just another integer in the crowd, had Trane not included him in his last recordings. (That’s no putdown of Sanders’ abilities, just recognition of the mundane fact that it’s not what you know, but who you blow with that counts.)

When exposed to him, many listeners found that Sanders did have more of a musical axe to grind than the average “promising player”, as well as a uniquely forceful way of honing it. In fact, some of the jazz wags were saying—just before Trane’s departure—that “Pharoah is saying it all, man; dig Meditations.” (The criterion, hardly justified, was Sanders’ stringency and stridency, comparatively more forceful than Coltrane’s neo-lyricism at that point.)

But Sanders is here—with his music. His compositions, even the heads—uncopable, in the latter-day manner that many onlookers, critics and plagiarizing musicians find so annoying (they say “so jive”)—are pillars of abstract continuity. They almost have to be played only by their composer because, as with so much of the best of the modern idiom, composition and exposition are inextricable; who else can sing Strange Fruit?

Lower Egypt is a rising bulge of sound—full of swirling piano, long reed swells, rattling temple blocks and bells— heaving with the powerful suggestion of birth, cresting subtly, then diminishing to a Grimes bowed passage. Sanders on piccolo is indebted to Sanders on tenor.

A rhythmic pattern, a montuna, emerges at a swift tempo to herald Upper Egypt. Against the regularity, Bettis places tricky percussion effects with, I believe, temple blocks or maybe boo-bams. A soaring Sanders enters on tenor. He builds away from the original line until, in less than a chorus, he finds ferocity. When the intensity subsides, he vocalizes with the rhythm.

Japan begins as gently impressionistic as a view of a Tokyo tea garden: little bells jangle against Sharrock’s guitar, strummed like a Koto, and Grimes’ soft harmony. There is a brief interlude of chanting by Sanders, more an impression than an imitation of the Japanese idiom.

Blank sets the tone for Aum (Om), also the title of the last Coltrane album, and it is frenetic. Sanders, on alto, collides with Sharrock in a pitched battle, pushing all the silent places out of existence.

The leader takes to his tenor again on Venus. Initially, he carves a sylph-like melody with that painfully beautiful tone of his. Then he begins to twist the line, fracture it, carve it up until it screams in torture. Burrell’s tumbling chords and the rumbling bass and percussion behind him add to the dynamics and gravity of this segment. Grimes and Sanders interlace like shoestrings to climax Capricorn, and one is again reminded of the poetry in Sanders’ tenor: the continuation of a song from joy through pain to peace.

A pianistic field holler begins Conquistador, the first of the Taylor album’s two sidelong tracks, both the leader’s compositions. The call is answered with a rush of horns and rhythm. Lyons’ line, beginning on a level of intensity several notches below that of the violent ground-swell supporting it, is somewhat buried within the buttressing folds of agitation. Ultimately, however, like a mountaineer, Lyons matches the summits of exertion around him.

When Dixon enters, the energy diminishes and his long, held tones are intermittently slashed by Taylor’s razor-edged chords. The tandem bass work is a dichotomy in arco and pizzicato.

Taylor’s solo is a masterful montage of rhythmically dominated fragments, laced together with myriads of 100-watt arpeggios—little Miro figures swimming brightly.

The flip side, With (Exit), opens with plastic skeins of music unwinding, unraveling to the puckering bow and exploding digits of Grimes and Silva. Again Dixon, with that haunted tone, slides whole notes across the air as if he were buffing antiques with a velvet rag.

Taylor’s tumbling, whirling, strobe-light pianistics are again a Herculean display of dynamic and textural virtuosity. Like John Henry, he never lets up; his music, the driven steel of inspiration, turns white hot before it’s over. His conception, admirably interpreted by the group gathered here, is thorny in perceptibility for some, since it has no fat couches on which the listener can lie and be entertained.

Intentionally or not, Albert Ayler ranks with the most sophisticated and satirical musicians of the decade, if one measures him by the “brevity is the soul of wit” equation. His best efforts, to this reviewer, are those of a genius because, in their simplicity, they tell the greatest of stories with a modicum of trivia attached.

Brother Donald has greatly improved over the last couple of years; either that, or his taste in recording companies has. The brothers’ musical interactivity suggests images in a house of mirrors, magnified and multiplied in a kind of cubistic situation wherein all sides of the phrase at any given moment are played as near simultaneously as possible. The cumulative effect is one of continuous revelry.

All the pieces on this disc are the leader’s. He apparently gave consideration to the possibility of airplay—if there are any imaginative and/or unrestricted deejays left in radioland. Each of the tracks on the first side is under four minutes long—some way under. Abbreviated versions of Ghosts and Bells, formerly waxed at epic length, strengthen this notion.

The title wedge, pure jubilation, is a call by the leader, echoed a second later by the trumpeter, in successive layers of ecstacy. Albert abandons his axe to chant the theme, as did Pharoah on Japan.

Dancing Flowers, featuring Albert alone in front, begins with a parody of Wayne King’s alto sound, tripping through the ricocheting vibrations of Cobbs’ harpsichord and the pulsating rhythm unit. Bells retains its happy, ringing instrumental chant. The theme figure races up and down, working its way out of a maze.

Love Flower is a plaintive tapestry decorated with filigree of harpsichord and percussion. Zion Hill is characterized by little circular movements and angular trips within the forward motion of the piece as a whole. It is similar to but less volatile than Cecil Taylor’s laminations.

Universal is a prolonged assault on apathy. Albert, proving kinship with Pharoah’s approach, furiously overblows at the top of the horn. He seems to want another register at the upper end and, finding none, forces the top one to extend itself to those heights anyway. A bugling Donald brackets Graves’ calibrated efforts and Silva’s bow-swoops, and dives to the returning onslaught of the front line.

These recordings are by four of the greatest and most diversified of the modernists. They are exemplary of the near past (Shepp), the present, and the future. Especially the future, because, though vilified by many “derriere-guardists”, they provide the grapes from which much of the watered-down wine of popular American music is made. The sad fact is that white all these men have a somewhat greater following in Europe, in a number of cases, the U.S. Bureau of Artistic Acceptance still pays its hacks to copy the work of its artists and present it in spayed versions.

—Quinn

(Bill Quinn)

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 157, July/August 1968, p.60) - France

albert ayler

Love cry : Love cry / Ghosts / Omega / Dancing flowers / Bells / Love flower / Zion hill / Universal indians.

Albert Ayler (ts), Donald Ayler (tp), Call Cobbs (clavecin), Alan Silva (b), Milford Graves (dm). New York, 1967.

Impulse A - 9165 / 33 t / 30 cm

1(0)/10 Il faut aller plus loin que l’humeur. Ces dernières années, le jazz, comme nombre d’éléments jusque-là tenus à l’écart et insuffisamment préparés, sera devenu un instrument de combat. (Jadis déjà, sur le mode de la confiance et de la bonhomie, les tournées du Département d’Etat.) Le jazz n’est plus un meuble de loisirs. Albert Ayler nous a dynamité tout ça, notre confort et nos illusions, avec un grand rire. Et tout un peuple d’incubes et de succubes, de démons et d’esprits, enfermés tenus en laisse dans les profondeurs inexplorées ou inexploitées des consciences, tout un peuple s’est levé, rugissant, brandissant l’étendard d’un monde parallèle. Ornette Coleman, ce prophète, avait esquissé un léger pas de danse, un pas de nymphe au pied mutin. Il n’était jamais allé aussi loin dans la mesure. Ayler, lui, a fait sonner la charge et, loin de la démesure, tente d’instaurer un ordre nouveau, quelque chose, une œuvre brouillonne, naïve et rouée, qui n’est pas seulement une contestation mais la négation d’un monde qui ne survit que par nos habitudes. Le jazz, voilà, s’est longtemps complu dans des ajouts à une matière minée, creusée de tant de galeries et de dédales souterrains qu’il a suffi d’un homme, armé de son saxophone et de sa bonne volonté, pour le foudroyer. Le bateau va couler, le bateau coule. Premier rat à l’abandonner, rat moins raté que les autres, Albert Ayler mêle en un sursaut originel, «préhistorique», les chants des Indiens Zuni aux sonneries altières du Débuché de Paris en passant par la Lorraine et Sambre-et-Meuse. Il brasse, pétrit, fonde ces éléments, cette mosaïque, en un magma tentaculaire, malmené à jet continu, traversé de part en part de grandes explosions de cris et de sons. Le bateau coule et les rats s’attardent. Ils ne musardent pas, ils raccommodent, tentent de colmater les brèches, chassant cette idée fixe et dévastatrice que tout est foutu. Ayler en a marre du passé du jazz. Il sait, lui aussi, reproduire de belles mélodies. Il l’a prouvé (My name is Albert Ayler).

L’air se raréfie. Il faut gagner les hauteurs. Là, bien campé, Ayler nous pète au nez. Et cette exhalaison immonde devient un souffle d’air frais.

Love cry, volet supplémentaire consacré aux thèmes répertoriés par Carles et Comolli, Ghosts, Bells repris, remaniés, réexplorés en de brèves volutes, en de brutaux encorbellements, épaulés par Omega, Dancing flowers, Love flowers, Zion hill, Universal Indians. Mais voilà. «UIysse»est une œuvre importante, Bells est une œuvre importante, mais nous ne pouvons pas en faire notre ordinaire. C’est pourquoi nous relisons «Le Rouge et le Noir» ou réécoutons Al Sears dans «Beautiful Indians».

— J.-P. B.

*

Kaleidoscope Chicago (Vol. 1, No. 10, March 28 - April 10, 1969 - p.18)

ALBERT AYLER, Love Cry, Impulse A-9165. Ayler, tenor sax; Donald Ayler, trumpet; Call Cobbs, harpsichord; Alan Silva, bass; Milford Graves, drums.

Albert Ayler, both in his personal conception and in the kind of band he has together, here, represents one of the most formidable solutions going to the “where-do-we-go-from-here-with-jazz” problem (if, indeed, its any problem for him at all). He chooses the path of freedom and innovation (he’s one of the most original musicians anywhere & his sidemen follow suit) and he’s steadily building a language both personal and universal, a quavering, sometimes agonizing sweet-sour sound which reveals magical depths and highlights.

The production strategy on this lp appears to be the same one that Impulse has pursued in “presenting” other former ESP-Disk artists to a “wider public”; cut down the lengths of the tunes, keeping the players from going too far out into improvisational fury. Even this can’t phase Ayler (a liberated cat, indeed); he still gets one side to work out on & for the first side, with its six two-to-four minute samplers, well, Ayler doesn’t degenerate into mere riffing, he showcases some of his more striking & beautiful melodies (“Omega” is one of the most joyous “Spanish” tunes I’ve heard in a while) and the group demonstrates a tightness in interplay which would do credit to most of the old dixieland groups. He even gets to work in some chanting (Moorish-Arabic-Oriental tinged) on the title track; after all, its “weird” enough to tickle the “hey, listen to this, will you” tourists, right? Ha ha. If you want to hear “Ghosts” done up proper, get ESP 1002, where he does two variations of it. “Bells” is the entirety of ESP 1010.

On side two, Cobbs begins “Zion Hill” with some Baroquish harpsichord & everything happening from there on to the end of the other cut, “Universal Indians,” is a joy to hear. Ayler has gotten himself together somewhat, lyrical strength that is one of the few valid replies to what Coltrane started. Brother Donald handles the trumpet masterfully & serves as a foil; his work on “Universal Indians” puts him out front among “new” trumpets, no news if you’ve heard him before, skittering like hell all over with deft abandon. Cobbs is the finest harpsichordist working outside “classical” music, and this is the first jazz or rock band to integrate that instrument. Silva is one more superb bassist, flashfire quick, & rich when he can afford to slow down. Graves is still one of the scariest drummers playing, at least as good as Rashied Ali, or Sonny Murray. When Keith Moon absorbs his message, or something like it, then maybe rock drumming will start to MOVE.

I’d have to pity anyone who cant get into this lp & groove hard with it. Really.

by Rich Mangelsdorff

Record Reviews

Discography: Love Cry

*

New Grass

The East Village Other (14 March, 1969 - p.13)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ann Arbor Argus (Vol. 1, No. 4, March 28 - April 11, 1969 - p.9)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Melody Maker (30 August, 1969 -p.19) - UK

Albert Ayler plays rock and roll . . .

ALBERT AYLER: “New Grass.”

Message From Albert/New Grass; New Generation; Sun Watcher; New Ghosts; Heart Love; Everybody’s Movin’; Free At Last. (Impulse SIPL 519).

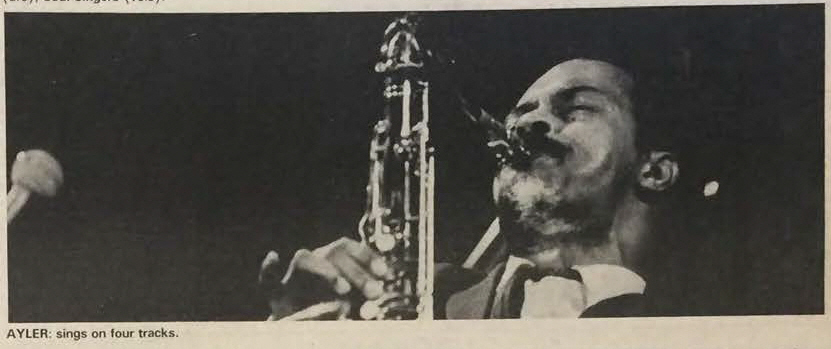

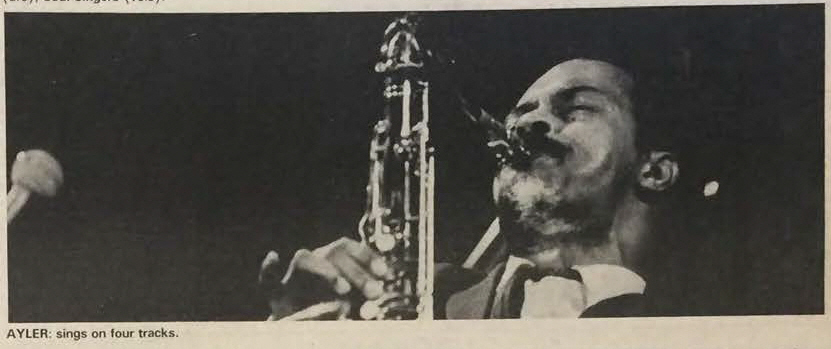

Ayler (ten/vcl), Burt Collins, Joe Newman (tpts), Garnett Brown (tbn), Seldon Powell (ten/flt), Buddy Lucas (bari), Call Cobbs (keyboards), Bill Folwell (elec.bs), Pretty Purdie (drs), Soul Singers (vcls).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THIS must be a very strong candidate for the Oddest Record of the Year Award. Pretty well throughout its length Albert Ayler, champion and hero of the avant garde, plays pure rock and roll — and the results are, to say the least, slightly amazing.

It would be easy to put this album down as the product of some A&R man's gimmick-laden brain, but one senses that it's something that Ayler himself really wanted to do — partly because he had a hand in composing all the songs, and partly because it's a direction in which he's always been heading.

Ayler stands with Archie Shepp in that he's firmly based in the pre-bop roots of jazz. His flirtation with the New Orleans march form showed that, and with "New Grass” he simply moves on to a slightly different tack.

The album opens with a brilliant duet between Ayler and Folwell, very much in the idiom of " Spirits" and "Holy Holy." Albert then recites a short message, telling us that he's been changed by meditation and that we should all seek love and peace.

Raucous

What follows, on "New Generation," is some of the best R&B tenor playing I've ever heard, with Albert sounding just as raucous and raunchy as those guys who played in Fats Domino's band of the Fifties. Anybody who thinks he can't swing should listen to this track.

Albert himself sings on four of the tracks, supported by the Soul Singers. He's no James Brown, but he gets the message over despite the essential corniness of much of the lyrics. "Heart Love" is probably the best of the vocal tracks, and would appear to have all the ingredients of a commercial hit.

"New Ghosts" is a four-square calypso thing with rocking tenor, while "Sun Watcher" has an ethereal organ-and-tenor intro followed by some solid riffing from Purdie and Folwell.

Despite all this, I feel that Albert is wasting himself on such material. He seems constantly to be trying to break loose from the rhythmic shackles imposed by Purdie, and I for one hope that he soon reverts to the magnificent music he was playing before "New Grass."

This album is worth investigating, but it's far from being the best of Ayler.

R. W. [Richard Williams]

*

Jazz Monthly (No. 177, November 1969) - UK

NEW GRASS:

Albert Ayler (ten); Bill Folwell (el-bs)

New York City September 5 and 6, 1968

New Grass

add Cal Cobbs (p); Pretty Purdie (d); Ayler (ten; vcl-1, whistling-2)

same dateNew ghosts - 1 :: Sun watcher - 2

Burt Collins, Joe Newman (tpt), Garnett Brown (tbn); Seldon Powell (ten); Buddy Lucas (bar); Rose Marie McCoy, Mary Parks (vcl - 3); Bert DeCoteaux (cond, arr); Cobbs plays organ, electric harpsichord; Ayler (ten, vcl -1, monologue - 4)

same date

Message from Albert - 4 :: New generation - 1,3 :: Heart love - 1, 3 :: Everybody’s movin’ - 1, 3 :: Free at last - 1, 3

Impulse SIPL ((m)MIPL)519 (37/5d.)

WELL HERE’S a thing. I guess that faced with a rock-and-roll album from a notable avant-garde musician one looks first for some kind of outside pressure: there seems to be none. Ayler wrote the material, sings, plays, talks and whistles, and in general shows every sign of having a good time. So then one looks for musical justification; if a man has his musical freedom he should be just as free to do something like this as something more sophisticated, and certainly in the past Ayler has made use of various Afro-American idioms in his music, the most notable I suppose being the New Orleans marching band bit, and more recently he’s used a lyrical method owing a fair amount to Johnny Hodges, but these folk-memories have in the past been considerably altered from their origins to fit an overall musical conception, while here the material hasn’t been subject to the same transformation. Rather the reverse: Ayler’s playing has been grafted onto a straight pastiche of the soul style, and though often the playing itself is good Purdie’s drumming is particularly finely detailed and very accomplished in its way the end result shows an uneasy mixture rather than any enriching of or development within the area of music that Ayler has in the past marked out for himself. Even so, it has its moments; some good, some heart-stoppingly bad. The best things come when there’s less people about, on the bass and tenor duet of New Grass, or on Sun watcher, both of whom offer new chances to study Ayler’s phenomenal high- register technique. But in general his thinking gets trapped in the beat and his playing hasn’t the fluency and logic of his best work. So in the end, while it’s nice to see the local Impulse boys finally letting some of Ayler’s work into the shops, one wonders why they chose this one and bypassed the Village Gate performances or the fascinating Love cry album available to them.

JACK COOKE

*

The Cricket (November, 1969) - USA

NEW GRASS/ALBERT AYLER

Personnel: Albert, tenor sax; Call Cobbs, piano, Electric Harpsichord and Organ; Bill Folwell, Electric bass; Pretty Purdie Drums, Burt Collins, Joe Newman Trumpets; Seldon Powell, tenor sax and flute, Buddy Lucas, baritone sax; Garnett Brown, Trombone.

Albert Ayler is one of the driving geniuses of the Music. He has clearly put forth a definite sound; a different and fascinating way of thinking about the world as sound; as movement; as the ghostly memory of the Spiritual Principle. Albert’s sound at its best is the field holler and the shout stretched like a piercing shaft from Alabama cotton fields to New York, and on into some cosmic world of strange energies. At his best, Albert’s voices buzz and hum with awesome deities.

When most of us first heard Albert, he really blew our minds, opening us up to not only new possibilities in music, but in drama and poetry as well. He was coming straight out of the Church and the New Orleans funeral parades. He had all kinds of Coon songs in his horn. He had compressed, in terms of pitch, all of the implied cycles in the blues continuum. His thrust was shattering. So that we must acknowledge that anything we say about this album must be seen against Albert’s fantastic possibilities.

But lately Albert’s music seems to be motivated by forces that are not at all compatible with his genius. There is even a strong hint that the brother is being manipulated by Impulse records. Or is it merely the selfish desire for popularity in the american sense?

At any rate, this album is a failure. It attempts to unite rhythm and blues dynamic with the energy dynamic of Ayler. But in attempting to unite the two styles certain very fundamental things have been overlooked. First, rhythm and blues is rooted in a popular tradition which has allowed for innumerable innovations in and of itself. It is a tradition that demands respect. Men like Jr. Walker demand respect. Because like Bird, they are the masters of a particular form. Therefore, any contemporary musician who attempts to use R & B elements in his music should check out the masters of that form.

Like it’s not too cool to get to the Rolling Stones or The Grateful Dead to learn things that your old man can teach you. And this is the feeling that I get from listening to New Grass. I mean the direct confrontation with experience as lived by the artist himself is not there. And this is a painful thing for me to say cause I have always dug Albert. I know what the Brother is trying to do. But his procedure is fucked up.

The rhythm on this album is shitty. There are no shadings, no implied values beyond the stated beat. The guitar is shitty. Most of the singing is shitty, especially the songs “Heart Love,” and “Everybody’s Moving.” The Sister sounds like she is straining, trying to find some soul in a dead beat. There are no kinds of nuianees on the drums. Hard rock, death chatterings. Albert should check out Jr. Walker’s band, or Bobby Blue Bland’s rhythm section. He should dig the long version of James Brown’s “There Was a Time.” He should note the heavy spiritual blueness in the bass guitar. He should dig how the rhythm and blues people embellish the beat, how they use space.

All this information is immediate. Most of the good bands come through the Appollo. This is where the discovery must take place, not in the context of white rock. This album strains at everything, even social consciousness.

But Albert’s attempt is fundamentally correct. It just must be focused sharper. The music must find ways of reaching into the pulse of the people; ways of taking ordinary elements out of their lives and reshaping them according to new principles. In this procedure, therefore, the music moves us toward national unity and spiritual unity. A Unity Music. A music that is so total, so fully informed by a Black ethos that it meets a more collective and less specialized need. Music can be one of the strongest cohesives towards consolidating the Black Nation. The music will not survive locked into bullshit categories. James Brown needs to know Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor, and Pharoah Sanders. I would like to see the Dells (“Stay in My Corner”), with Pharoah or Archie Shepp. Implied here is the principle of artistic and national unity; a unity among musicians, our heaviest philosophers, would symbolize and effect a unity in larger cultural and political terms. Further, there should be more attempts to link the music to other areas of the Black Arts movement.

LIKE: REVOLUTIONARY CHOREOGRAPHERS LIKE ELEO POMARE,

JOHN PARKS, JUDI DEARING, TALLY BEATY SHOULD BE

CHECKING OUT CECIL TAYLOR’S MUSIC WHICH IS

HEAVILY POSITED ON DANCE CONCEPTS.

*************************************

HOW DOES POETRY AND MUSIC OPERATE IN THE CONTEXT

OF POLITICAL AND RELIGIOUS

GATHERINGS?

*************************************

PHAROAH NEEDS A TEMPLE.

SUN RA IS A BEAUTIFUL BLACK INSTITUTION.

*************************************

POETS SHOULD WRITE SONGS

*************************************

And so on. Back to Albert, The so-called New Music represents at the core of its emanations the philosophical search of Black people for Self-definition. Unlike the blues, its placement is more directed at our possibilities in the cosmic sense. Every aspect of the music can feed on the other. There are still a myriad of possibilities for musicians in the area of the human voice. Max Roach and Donald Byrd showed the way; and there is still a lot of space left as Coltrane, Pharoah, and Albert indicate.

There are some profound possibilities in the area of tribal chorus. (Check out volume two (2) of the World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, Columbia, KL-205) But these possibilities, as relevant as they are, will not be realized if we approach them as gimmicks adopted from jive white boys. What we will get in that case will be bull-shit “universalism.”

Albert you are already universal. You were universal when you cut My Name is Albert Ayler; and even there the context was bad. Swedish nightmares. If you speak to your Brothers and Sisters, to us who really love, and care not just for you, but for us, you will be in fact universal. Check out your context black musicians. Who is your primary audience? Ed Sullivan, Janis Joplin, timothy leary ....? Or are you about something that relates to us; and even though we be slow in digging you sometimes, just the fact of you being nearby, around the corner; we all working it out together, reaching for that Unity Form; just this fact alone deepens communication and strengthens in a concrete spiritual manner.

GREAT SPIRITS, HELP US TO SEE AND HEAR

ASANTE

Larry Neal

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 171, 1969, p. 43) - France

[click the picture below for a readable version]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coda (January, 2005) - Canada

A WHOLE LOT OF CANNONBALL,

FANTASY 20-BIT REMASTERS,

V.S.O.P., ALBERT AYLER’S NEW LEAF

BY DUCK BAKER

...

The 1968 release of Albert Ayler’s New Grass (Impulse 000426902) was an unwelcome, almost depressing event that seemed to bear witness to the loss of direction by one of John Coltrane’s principal followers following his death. This seemingly impossible attempt to bridge the chasm separating free jazz and soul R&B sounds considerably better now than it did at the time: New Grass may not have been a wholly successful experiment but it does have interesting and very convincing moments.

*

Jazz Journal International (Vol. 59, No. 8, August 2006, p. 17-18) - UK

ALBERT AYLER

NEW GRASS

(1) New Grass / (2) Message from Albert; (3) New Generation; (4) Sun Watcher; (5) New Ghosts; (3) Heart Love; Everybody’s Movin’; Free At Last (33.09)

(1) Albert Ayler (ts); Bill Folwell (b); September 5 or 6, 1968; NYC (2) add Ayler (recitation); Burt Collins, Joe Newman (t); Garnett Brown (tb); Seldon Powell (f); Buddy Lucas (bar) (3) add Call Cobbs (elp); Bernard ‘Pretty’ Purdie (d); Ayler, The Soul Singers (v) (4) Ayler (ts, whistling), Cobbs (p, org); Folwell (b); Purdie (d) only (5) add unknown (tambourine)

(Impulse 0602498842195)

Historians may decide that Albert Ayler’s primary contribution to jazz was to prove that the saxophone was capable of the kind of tonal variation usually only produced by brass players manipulating mutes. Certainly the control of this aspect of his playing is remarkable on this CD but it’s not matched by similar imagination of phrasing, which seems to be based on either very simple motifs or standard chromatic flurries. In this later stage of his career he was combining that with contemporary rock rhythms and some sadly banal lyrics related superficially to religion. His singing in a high-toned tenor voice contrasts with the rough-hewn saxophone sound which, as has often been pointed out, derives from the rhythm- and-blues honkers. New Ghosts, once the vocal introduction is out of the way, presents a logically developed tenor solo over a calypso rhythm and is the most successful track but, in keeping with the overall brevity, it fades out with Ayler in full flow. Elsewhere the poverty of the material and the frequent divergence between Ayler’s abstractions and the over- simple support means that only dedicated Ayler collectors are likely to be interested in this and they would surely prefer the release of his more uncompromising recordings.

Graham Colombé

*

Online Reviews:

‘New Grass’ by Ken Waxman - JazzWord 2/13/2006.

‘Graded on a Curve: Albert Ayler, New Grass’ by Joseph Neff - The Vinyl District 6/30/2020.

Record Reviews

Discography: New Grass

*

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe

Jazz Monthly (No. 186, August 1970) - UK

MUSIC IS THE HEALING FORCE OF THE UNIVERSE:

Albert Ayler (ten-1, bagpipes-2); Bobby Few (p); Henry Vestine (g); Bill Folwell (bs, Fender-bs); Stafford James (bs); Muhammad Ali (d); Mary Maria (vcl-3)

New York City August 26, 27, 28 and 29,1969

Music is the healing force of the universe - 1,3 :: Masonic inborn, part 1-2 :: A man is like a tree - 1,3 :: Oh! love of live - 1,3 :: Island harvest - 1,3 :: Drudgery - 1

Note: Double-tracking by bagpipes on Masonic inborn and by guitar on Drudgery

Impulse AS-9191 (59/6d.)

A LOT OF WHAT happens on this album relates in some degree to the ideas first expressed on Ayler’s New Grass album (Impulse SIPL 519, reviewed November 69). Here, however, the rock beats have been replaced, except on Drudgery, by more familiar, fragmented methods; the vocal group has been dropped along with the studio band, though the song principle remains with Mary Maria’s work. But having got away to a large extent from the limiting rock format Ayler seems to have found himself in a no less awkward situation here, and though much of his old force of expression remains it gets dissipated and loses all effect in this new setting. On the vocal tracks he plays up to Mary Maria without ever telling us anything we didn’t know about his style already; the singer herself reveals a powerful voice but not much subtlety. The material is by Ayler and Mary Parks, the New grass team; a familiar series of melodic shapes emerges but the less said about the banal, inflated lyrics the better. Island is a bit of an oddity within the context, a calypso novelty complete with BWI accents, but nothing very satisfying emerges from it, while Drudgery reverts to instrumental format with a rock beat, and a solo from Ayler that sounds as though he’s auditioning not too successfully for a job with an organ combo.

Which brings us to Masonic, a 12-minute workout on bagpipes complete with overdubbing to maintain the wall of sound. I can’t find anything here that’s very enjoyable; the instrument itself is certainly capable of producing some pretty unique sounds, and Ayler makes the most of this, but its severely limited in many other other ways and the performance as a whole, notwithstanding the obvious energy that went into it, is neither organised nor developed in any useful way.

So it’s a pretty scrappy album, far from being Ayler’s best or even good at all by his standards. There was in his best work still is a quality that I can only describe as revelatory: the truth often was marching in with his music. It’s not evident here, and on present evidence doesn’t seem likely to come back until some changes are made somewhere. So at three quid a go one can only say caveat emptor.

JACK COOKE

Record Reviews

Discography: Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe

*

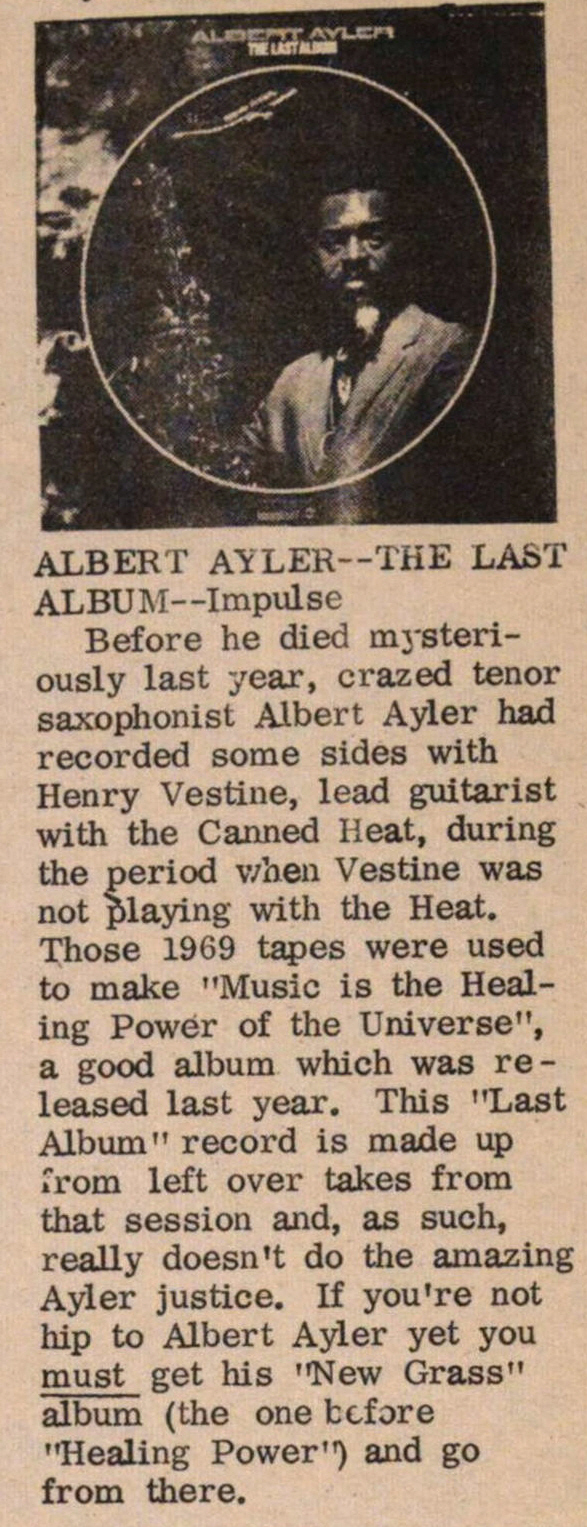

The Last Album

The East Village Other (14 July, 1971 - p.10)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jazz Magazine (No. 191, August 1971) - France

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

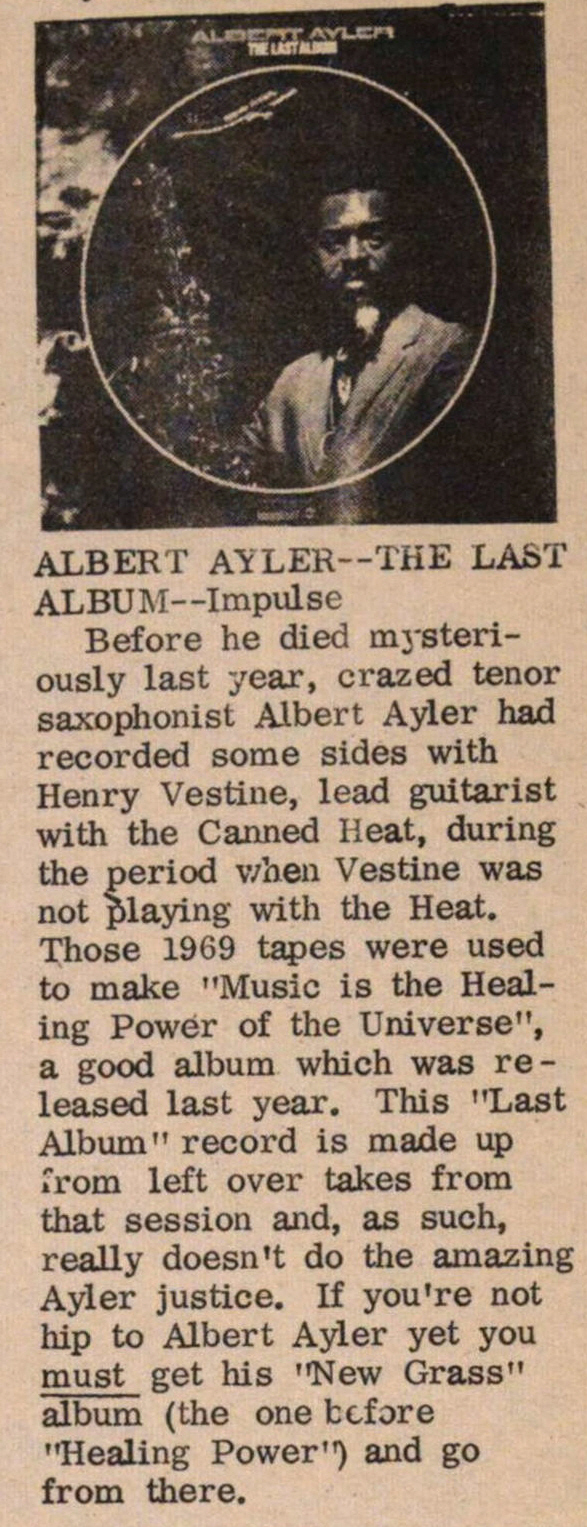

Ann Arbor Sun (17 September, 1971 - p.12) - USA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Record Reviews

Discography: The Last Album

*

Next: Holy Ghost

|

|

|

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

|