|

|

|

|

|

Record Reviews 3:

New York Eye And Ear Control -

Lorrach/Paris 1966

|

|

|

|

|

|

New York Eye And Ear Control

Ghosts

The Hilversum Session

Bells

Spirits Rejoice

Sonny’s Time Now

At Slug’s Saloon

Lorrach/Paris 1966

New York Eye And Ear Control

Jazz Magazine (No. 141, April, 1967, p.48-49) - France

albert ayler

New York eye and ear control : Don’s dawn - AY - ITT.

Albert Ayler (ts), Don Cherry (tp), John Tchicai (as), Roswell Rudd (tb), Gary Peacock (b), Sunny Murray (dm). New York, 17 juillet 1964.

ESP 1016 - 33 t - 30 cm.

6/10 La note qui précède n’est pas le fruit d’un jugement. Il ne saurait y en avoir de raisonnable en cette matière tant qu’on n’a pour tout critère qu’une certaine qualite d’émotion. C’est celle-ci qui est appréciée, comme une mesure thermométrique, à ceci près que l’instrument, lui, donne la même mesure pour tout le monde. On peut aussi juger le free selon ses intentions, sa philosophie, ses hommes et leurs idées; ce qui est certain, c’est qu’on ne peut pas — encore — le juger selon des valeurs purement musicales à moins de redéfinir la musique en en assouplissant les concepts, en les «généralisant» (opération suivant laquelle une constante devient variable), et en en reculant les limites indéfiniment.

Ayler, dans ce disque (bande sonore d’un film de Michael Snow portant le même titre) comme ailleurs est poursuivi par sa passion de la révolte absurde. Il ne condamne rien, il ne met pas en rnusique une théorie politique ou sociale, il ne met pas en cause d’anciennes conceptions musicales, il délire pour délirer, sans plaisir ni haine, mais à bout-pourtant, avec une espèce de sauvagerie naïve, une colère sans humeur qui referme sur lui-même la négation qu’il nous lance à la face. Lorsque ce père Ubu saxophoniste a mis tout le monde à la trappe, il s’y balance lui-même, avec une espèce de frénésie joyeuse. Cette musique est l’emphase de la vanité, une insolente et bruyante absence; tout se passe comme si elle voulait extirper le mot signification du vocabulaire des musicologues. Sa tactique, c’est de décevoir, de n’accepter ni conciliation ni réconciliation. Elle n’aime personne; surtout, elle voudrait que personne ne l’aime. L’amour qu’on reçoit rend esclave. Elle veut être libre, n’appartenir à personne, d’où cette fureur qu’elle met à se détruire sans cesse, cette terreur de faillir dans la beauté et d’y être retenue prisonnière. Chez les primitifs parfois, pour éloigner les mauvais esprits, on fait grand tapage. La nuit durant, autour des cases, on mène un combat terrible contre un ennemi invisible. Ayler et ses amis, d’une semblable manière, donnent à leur vacarme valeur d’exorcisme. Ils conjurent leurs démons (ce jazz qui les asservit à leurs admirateurs), vainqueurs s’ils ont pu hurler plus fort que leurs tentations. Formidable lutte contre soi où l’on ne sait trop à la fin si l’on a triomphé de 1’aliénation ou si l’on s’est acculé au néant. Parfois, saisis d’un doute, ils cèdent et laissent échapper quelque mélodic purement (presque classiquement) belle comme ces quelques mesures de Cherry dans un extraordinairement bref Dons Dawn. Cette faiblesse à mes yeux suffit à leur trouver quelque grandeur.

Comme tous les grands clowns, ces clowns musicaux posent l’interrogation désespérée de 1’homme absurde face à une liberté qui semble vouloir le mettre nu pour mieux l’assassiner.

— A. G.

Record Reviews

Discography: New York Eye And Ear Control

*

Ghosts (aka Vibrations)

Jazzwereld (November, 1965) - Netherlands

,,Ghosts”

Ghosts - Children - Holy Spirit - Ghosts - Vibrations - Mothers

Albert Ayler (ts), Don Cherry (kornet), Gary Peacock (bas), Sonny Murray (drs).

Kopenhagen, sept. 1964

Fontana 688 606 ZL (mono)

ƒ 18.50

* * * ½

Diskussies over ‘the new thing’ hebben vaak een wet wazig karakter, doordat deze snel geaksepteerde term een zo wijd gebied bestrijkt. Het is moeilijk om zinnige argumenten (pro of kontra) te vinden die algemeen toepasbaar zijn op Ornette Coleman én George Russell én John Coltrane én Don Ellis én Archie Shepp én Paul Bley én Cecil Taylor én Albert Ayler enz. Nog onvruchtbaarder wordt het gesprek wenneer men erover gaat twisten of pakweg. Miles, Mingus, Gil Evans, Rollins of Andrew Hill nu wel of niet onder ‘the new thing’ vallen (sterk staaltje: „Henry Red Allen is the most avantgarde trumpet player in New York City” by Don Ellis, in Down Beat van 28 januari ’65).

Supporters van ‘the new thing’ verwijzen graag naar de bopperiode, toen immers vele kritici, fans en musici aanvankelijk heftig tegen het nieuwe ageerden, maar later wel degelijk het meesterschap van Parker, Gillespie en Powell moesten erkennen. Deze historische terugblik wordt dan veelal gehanteerd als bewijs voor dv waarde van ‘the new thing’, een stukje logika (er zijn mensen tegen, dus het is goed, want vroeger waren ook mensen ergens tegen en die kregen ongelijk) dat mij ontgaat. Bovendien was de bop een duidelijk omschreven genre waar men inderdaad integraal voor of tegen kon zijn, terwijl ‘the new thing’ zoals gezegd een enorme verscheidenheid van muzikale opvattingen omvat (ik kan me bijvoorbeeld levendig voorstellen dat iemand wel door Coltrane en niet door Ayler geboeid wordt, maar mensen die van Parker houden en Powell verafschuwen lijken me dungezaaid). Ik wil maar zeggen dat vergelijkingen gevaarlijk zijn en dat we gekompliceerde tijden beleven. De hieronder volgende opmerkingen over dv nieuwe Ayler-lp dienen dan ook te worden gelezen als opmerkingen over de nieuwe Ayler-lp en dus niet als een uiteenzetting van mijn privé-theorie over ‘the new thing’.

Ayler kwam vorig jaar november als volslagen onbekende naar one land. Zijn konserten en radio-opnamen leidden toen tot verhitte diskussies die tenslotte eenvoudig doodliepen doordat niemand zich meer precies herinnerde hoe Ayler c.s. nu eigenlijk hadden gespeeld. De lp ‘My name is Albert Ayler’ was dan wel op de markt, maar die gaf een zo verwrongen beeld van Aylers kapaciteiten dat men er bezwaarlijk een oordeel over zijn muziek op kon baseren. Dv nieuwe Ayler-lp (nieuw voor Nederland wel te verstaan, in de VS zijn al recentere platen van hem verschenen) is gelukkig wel representatief voor het stadium waarin de saxofonist tijdens zijn Nederlandse tournee verkeerde. Ayler en zijn mannen hebben niet alleen het keurslijf van akkoordenschema of toonreeks radikaal doorbroken, op ritmisch gebied laten ze nog veel verrassender dingen horen. Er bestaat wel een tempo, al wisselt dat vaak, maar de maatindeling is verdwenen. Drummer Sonny Murray verdeelt de tijd en dat is alles; de gebruikelijke indeling in meer en minder geaksentueerde tijdsdelen wordt losgelaten. Peacock hoeft zich als begeleider niet meer te bekommeren om het vier- in-de-maat en is evenmin gebonden aan bij het thema behorende harmonieën. De solisten zijn dus ‘vrij’, wat niet betekent dat ze er maar in het wilde weg op los kunnen spelen. De ‘vrijheid’ is voor hen een opgave die moet worden vervuld. Wanneer het thema is gespeeld, staan ze voor een leegte die ze niet kunnen vullen met roetineloopjes over de changes. Ze stellen zichzelf de zware taak, louter met spontane ideeën boeiende muziek voort te brengen. Ze moeten, willen ze slagen, voortdurend geinspireerd zijn. Vakkundig routinewerk (zoals we dat bijvoorbeeld tijdens het merendeel van de nachtkonserten te horen krijgen) is binnen deze manier van muziekmaken nauwelijks mogelijk; als de inspiratie wegvalt blijft er maar heel weinig over.

Ghosts is een goed in het gehoor liggend melodietje, dat het midden houdt tussen een kinderliedje en een calypso. Het wordt op de eerste kant kort als tune vertolkt; de versie op kant twee bevat ook improvisaties. Ayler begint zijn solo met een variatie op flarden van het thema, maar gaat al spoedig over op snelle, opgewonden frasen waarin nog slechts af en toe een herinnering aan het thema opduikt. Ook Cherry’s solo bestaat grotendeels uit snelle, nerveuze loopjes. Een herhaling van het thema leidt tot een gestreken bassolo, waarin Peacock met ongebruikelijke middelen (zeer snelle rechterpolsbewegingen, hoge flageolettonen) een verrassende verwerking van het thema geeft. Het stuk eindigt met een tweede herhaling van het thema.

Children bevat onder meer een gezamenlijke improvisatie van kornet en tenor, en een getrokken bassolo met zeer lang doorklinkende noten en passages die aan Spaanse flamenco-gitaristen herinneren. Holy Spirit is een langzaam, plechtig stuk, waarin Ayler vooral het hoogste register van zijn instrument exploreert en Cherry krachtiger en technisch gedurfder speelt dan men bij Ornette van hem gewend was. Het snelle Vibrations is gebouwd op een eerst even dalend en dan stijgend figuurtje (vgl. de eerste maat van 52nd Street theme, zonder de dalende terts aan het eind) dat in de improvisaties voortdurend terugkeert. Ayler vertolkt het klaaglijke Mothers met een enorm vibrato en met onverhuld sentiment dat fondantachtig noch sarkastisch aandoet. Hij bewijst er tevens mee dat hij zijn instrument wel degelijk beheerst. Cherry blaast een sterke, zekere solo, hoofdzakelijk opgebouwd uit lange noten. Peacock grijpt in zijn gestreken solo weer herhaaldelijk terug op het thema. Ayler besluit het stuk met zijn thema-parafrase, ondersteund door Cherry’s hoge kreten.

Na de beschrijving hoort dan nu de beoordeling te volgen. Mijn sterrenaantal wijst er al op dat het oordeel niet onverdeeld positief is. Dat betekent niet dat ik de prestaties van Aylers musici wil kleineren. Integendeel, ik heb ontzag voor de manier waarop ze een deel van de door henzelf opgeworpen problemen hebben opgelost (ritmiek, taakverdeling solist-begeleiders, Aylers toon-experimenten). Alleen zijn er mijns inziens ook nog problemen onopgelost gebleven, zoals dat van de eenheid, de homogene opbouw van een stuk. Op deze lp worden soms fragmenten van het thema gebruikt als bindend element in de improvisaties; naar mijn smaak zijn die stukken (Ghosts, Vibrations) het meest geslaagd, maar misschien ziet Ayler ze juist als nog te overwinnen restjes konventionaliteit, en vindt hij in de toekomst nog een geheel nieuwe oplossing van dit probleem.

In elk geval is ‘Ghosts’ een plaat die een aandachtige beluistering meer dan waard is, als boeiend stadium in een nog voortgaande ontwikkeling.

BERT VUIJSJE

[click here for the original page]

*

Jazz Hot (January/February, 1966) - France

GHOSTS

Ghosts • Children • Holy Spirit • Ghosts • Vibrations • Mothers •

FONTANA 688 606 L (30 cm - 26,90 F)

****½

Don Cherry (tp); Albert Ayler (ts, as); Gary Peacock (b); Sonny Murray (dm).

Il est bien difficile de parler de ce disque: il y a trop à dire. Dire d’abord qu’il n’est pas sans défauts, que tout n’y est pas parfaitement équilibré, que les intentions ne sont pas toujours satisfaites. Mais dire surtout qu’il y a autant de musique ici que dans les meilleurs disques des plus grands musiciens du jazz. Ne pas oublier de prévenir non plus: cette rnusique ne sera jamais facile. Il n’est pas question d’ “habitude de l’oreille” mais plutôt du contenu expressif qui est d’une telle densité qu’on peut assurer que c’est par rapport à ce contenu que l’auditeur se placera dans son refus ou son acceptation.

Cet enregistrement se caractérise par: des thèmes naifs, aux accents folkloriques, utilisés en fragment dans les improvisations qui sont plutôt de caractère thématique mais pas nécessairement; tempi non fixés pouvant changer en cours de morceau et non métronomiques; pas d’obligation de swinguer tout au long du morceau (le batteur, de toute façon, ne joue pas de façon classique); vague centre tonal qui disparait avec l’emploi systématique de notes non situées sur la gamme tempérée ou trop riche en harmoniques pour être bien situées ; valeur de ces fluctuations entre la tonalité et le manque de localisation de la tonalité, enfin, utilisation de sonorités nouvelles obtenues par divers procédés (large vibrato dans “Mothers”, harmoniques dans “Vibrations”, etc.).

Le plus remarquable. c’est l’expressionnisme de cette musique, qui n’a jamais été approché par qui que ce soit. A cet égard, “Mothers”, le morceau le plus choquant de l’album du point de vue des sonorités, si étrangères au jazz, est le plus significatif.

Albert Ayler est bien le moteur de cet orchestre et ses improvisations ont la logique des cataclysmes. Sonny Murray, transfuge de la formation de Cecil Taylor, est en train de trouver la voie qui libérera les batteurs de leur fonction métronomique. Gary Peacock ponctue très intelligemment ce qui semble ne pas être articulé et, comme soliste, devient de plus en plus intéressant. Don Cherry est partout, ses brusques interventions ont parfois une valeur purement rythmique; il a su adapter à ce style le contrechant du jazz classique. Comme soliste, il doit oublier son manque d’assurance technique par la vivacité de son imagination. Remarquez son solo de “Holy Spirit”, si “blanc” de sonorité, si recueilli.

Albert Ayler, même s’il se réclame du spiritisme (sainte publicité !), n’a d’autre but que d’exorciser les coutumes sacrées de la musique. En sapant les règles, il espère trouver la fraicheur du chaos originel, sans clichés, sans habitudes formelles, sans nécessité d’adhésion à un beau préexistant. On a vu que, pour ne pas tomber dans le néant, il a été amené à créer un nouveau système de références (ne serait-ce que par l’interdiction des formes anciennes) qui lui permet d’exprimer sa propre vérité. Seul le radicalisme de ses conceptions le sépare des autres novateurs du jazz, et sans doute le système devra-t-il rester en mouvement ou disparaitre. La musique ne reflète que la musique et, même pour exprimer un sentiment révolutionnaire, Albert Ayler ne pourra échapper au monde des sons.

Il prouve en attendant la richesse du jazz d’aujourd’hui.

Pierre LATTES.

*

Jazz Monthly (March, 1966 - p.20) - UK

GHOSTS:

Don Cherry (cnt); Albert Ayler (ten, alt); Garry Peacock (bs); James “Sonny” Murray (d)

Copenhagen—September 1964

Ghosts : : Children : : Holy spirit : : Ghosts : : Vibrations : : Mothers

Fontana 688 606 ZL (33/1d)

(The above LP is an import and can only be obtained from specialist jazz dealers)

IT SEEMS THE TIME has come for me to sit down and not be counted, if you see what I mean. I don’t rejoice in this fact, since I am only too well aware that my opinion may change, but for the moment I am not unduly impressed by this record. It was made in Denmark by the group which Michael James heard in Amsterdam and reviewed in our January 1965 issue, and one can say right away that it is less terrifying to listen to than it was to read about. It is perhaps the best Ayler album yet, by which I suppose I mean the least boring, and there are some quite pleasant moments; in particular, Don Cherry, whom I always found difficult to swallow despite the high praise awarded him by Rollins and Coleman, now seems to have a clearer conception (if not any greater instrumental control). However, there are several questions which worry me about Ayler’s music:—Where is the connection between the naivety of his themes and the primitivism of his solo work (the grotesque guying of the thematic phrase immediately after the theme statement on the second version of Ghosts provides little clue)? Does it matter that the unison theme statements are sometimes so approximate that they are not in unison? Has Ayler got through to me if, of the six tracks here, I prefer the shorter, calypso-like version of Ghosts, which is all theme statement? Why does he record so many different versions of Ghosts, and why doesn’t he call it The foggy, foggy dew and get in on the Folk boom?

As Charles Fox said recently, in so many words, the only trouble with most of the “new thing” is having to listen to it. I never found any problem in accepting the idea of “free jazz” intellectually, and I find most of the arguments used against it to be fallacious. To describe it as “anti-jazz” is definitely out, if only because the term “anti-novel” was employed ’way back in 1839! To say that “They don’t know what they’re doing” is illogical, because the statement merely proves that the listener doesn’t know what they’re doing. And it’s no use saying, for instance, that Albert Ayler’s tone is patently ridiculous, because so is all jazz to the genuine outsider; all the most moving noises which we treasure mean nothing to millions of people. Even with the most basic vocal music, the sound of Bessie Smith bellowing is as incomprehensible and potentially embarrassing to the uninitiated as the sound of Edith Piaf emoting. In fact, however much some jazz writers may attempt to deny or ignore the fact, the only way in which appreciation of any kind of music can be cultivated or deepened is by the realization, whether conscious or unconscious, of the musical laws by which it is governed. I just wish someone would tell me what laws govern Ayler’s music.

BRIAN PRIESTLEY

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 135, October 1966, p.55) - France

[Combined review]

*

Jazz Monthly (No. 179, January 1970) - UK

GHOSTS:

Don Cherry (tpt); Albert Ayler (ten); Gary Peacock (bs); Sunny Murray (d)

Copenhagen, Denmark — September 1964

Ghosts (2 versions) :: Children :: Holy spirit :: Vibrations :: Mothers

Fontana SFJL 925 (28/7d.)

AYLER’S MUSIC was at a rather early stage of development when this was made, and it had at this time a remarkable purity of style; it was non-European in its elements, though it had not yet incorporated some of the more conscious primitivism that came later; it was rich melodically and rhythmically, easily approachable through the simple song-forms of the theme lines, yet demanding in the concentration it asked of listeners once the performance got under way. Ayler’s own playing was that of an exceptionally talented and original musician, unusually inventive in his solos, a technician of immense skill, with a quality and range of tone that began to defy description. He was supported by a fine bassist and a brilliant drummer who stuck with him for a long enough period to become totally convincing in what they did; adventurous in themselves, yet so completely a part of the whole that their innovations were at times mistaken for more conventional responses than they actually were. Into all this Don Cherry fits extremely well with his bright sound and sharp-angled lines; his solos are good and along with Ayler he provides a feast of invention and wit. It’s hard, in a few words, to say much about the tracks individually, and indeed it’s not entirely necessary; there is such consistency here, together with a prodigality of detail. One’s interest is completely sustained, first to last. This is highly recommended.

JACK COOKE

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 220, March 1974) - France

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ann Arbor Sun (11 April, 1975) - US

[Click the picture for a readable version.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From The Essential Jazz Records: Modernism to Postmodernism by Max Harrison, Charles Fox, Eric Thacker and Stuart Nicholson. (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000) - UK

Albert Ayler

408 Vibrations

†Black Lion/Freedom (E) 741000

Don Cherry (cnt); Ayler (alt, ten); Gary Peacock (bs); Sunny Murray (d). Copenhagen, 14 September 1964.

Ghosts (2 versions) - Children - Holy spirit - Vibrations - Mothers

Ayler was nobody’s jazz disciple. The chronicler of Ornette Coleman’s adventures has claimed that Ayler ‘was a successor . . . who pushed aspects of Coleman’s discoveries to extremes’. But no voice heard in jazz has been more singular than Ayler’s, or more facilely misapprehended. The voice is unmistakable in its startling intonation and sometimes fearsome force. How much did its acquisition have to do with a genuine quest for style? And to what extent is Ayler’s music to be assessed within the purview of ‘free’ or ‘post-Coleman’ jazz? The trail that led to his conception of himself as a ‘spiritual artist’, if investigated, assists an evaluation of his relation to any jazz tradition only fitfully. Boyhood links to black church music, and a reported mastery of bop techniques, remain enigmatic, even though some hearers have discerned echoes of ‘primitive’ jazz, and even though some boppish shreds clung to his first recorded evidence of personal mode (The First Recordings, †Sonet [D] SNTCD604). That maverick session from late 1962 showed some regard, in programme choice, for jazz exemplars, yet the already vicious, calculated ugliness of sound in his tenor expostulations might be thought to steal some of its bleak rawness from the overtones of amplified rhythm-’n’-blues saxes, harmonicas and guitars. Ayler had been a teenage rhythm-’n’-blues sideman on the alto back in Cleveland and it is an open question whether his return to a blend of gospel and rhythm-’n’-blues near the end of his life was a jazz visionary’s sad capitulation or a repayment of old debts by a man still capable of artistic choice.

This Vibrations programme, recorded, like the Sonet issue, in Copenhagen but with more congenial companions, has appeared in various guises, otherwise titled Ghosts and Mothers and Children. Like the incongruously programmed, strangely manned yet revelatory My Name Is Albert Ayler (Fantasy [A] 86016, Fontana [E] 688 603ZL), recorded the previous year, this album finds Ayler still probing half-excavated ideas and benefiting greatly from the empathy of Cherry, Peacock and Murray. That musical camaraderie may seem partially to answer the question about Ayler’s relation to free jazz - Ayler and Murray also had worked with Cecil Taylor in Europe. However, the association with a Cherry who was at the point of making his own post-Coleman foray beyond the possible ‘restrictions’ of too close a jazz identification must have been one of Ayler’s happier options. The telling, unaleatory melodic alliance between the two leading voices in the ‘foggy dew’ ruralism of Ghosts - not the only Ayler creation which merited Cherry’s description of him as ‘a total folk musician’ - is one of the session’s most instructive features. The second, much lengthier, version of Ghosts is approached obliquely at first. It has some jokey disjunctions from Ayler, along with those kinds of grossly sustained bellowing which, offensive as they seemed, continued to be part of this player’s way of pursuing a strain of Stygian lyricism.

That paradox is also present in the tenor assaults in Vibrations, where the shades of the unexpressed beauty which this jazz mystic professed to seek have to be discovered within an extended sequence of new-wave exhibitionism, arguably close kin to Coleman’s Free jazz (400), passages where self-challenge too easily leads toward the species of artistic hara-kiri which was to prove irresistible to Coltrane and his kindred. To Ayler’s tirades Cherry adds little other than exclamation marks, but the full quartet is busily involved. Peacock’s work is, as elsewhere, more sensitive and poetic than that of anyone other than Murray. It is Murray who stuns Vibration’s wildness with one peremptory cymbal smash.

Holy spirit begins as apocalyptic dirge-making, and already poses the ‘jazz primitivism’ question. The tempo-negating undertow of drums and bass nurtures patterns alternative to the soliloquies and unisons of brassy alto and serenely poised cornet. Lullaby and domestic balladry seem to inspire Ayler’s tunes for Children and Mothers. Cherry’s keen knowledge of Ayler’s intentions is marked in Children. His close commentary, in a mode less speech-inflected than that of his Coleman solos, helps in developing some attractive duet passages. In Mothers, having bumbled and nattered beneath Ayler’s querulous lamplit serenade, he counters that theme with another built of clear, loftily sustained notes; a tune quite different, and, for what it seems to matter, not jazz in any known style. After that Peacock reintroduces Ayler’s tune in the cellar beneath the parlour; but the leader’s mock-maudlin piety has the final say.

Ayler’s collaboration with Cherry is the first high point in his recording career. How far it goes in establishing his jazz status is not easy to measure, despite its undeniable fascinations. The later groups involving Ayler’s brother Donald and the violinist Michel Sampson pose the enigma quite differently. The sextet to be heard in 409 provides an intriguing set of examples for consideration. For those, Vibrations should seem the right kind of preamble, showing this saxophonist as a natural - though not intellectualist - analyser of sounds, and at the same time an ecstatic eager to claw his way inside some sensed essence of a music which had been his milieu and his formation. The last thing to doubt, at any stage, is the man’s sincerity.

Eric Thacker

Record Reviews

Discography: Ghosts

*

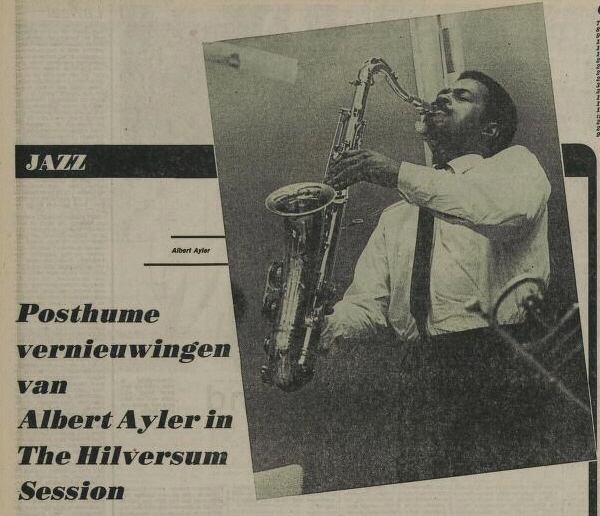

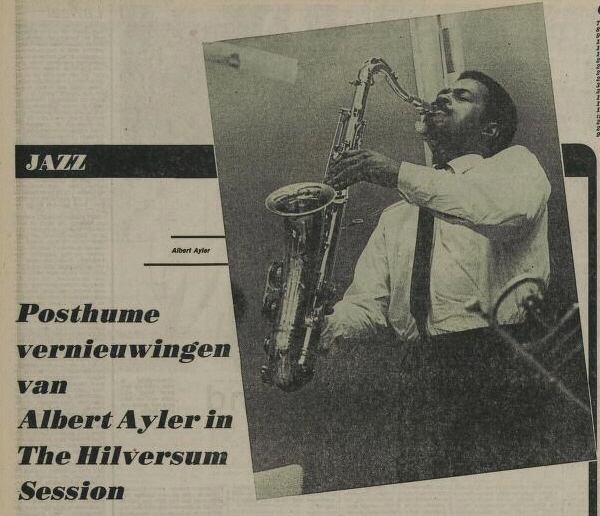

The Hilversum Session

[Bert Vuijsje’s article about the recording session (published in Vrij Nederland on 5th December, 1964) is available in the Articles section, translated into English by Kees Hazevoet.]

Melody Maker (31 January, 1981) - UK

Life being short and the vinyl flow unstemmable, I don't suppose I had listened to Albert's music for a year.

One shot of this previously unreleased material sent me burrowing back into the Ayler oeuvre in wild excitement. Could there be anything as good as this? Possibly Spirits, possibly Ghosts, possibly Spiritual Unity; quite possibly, this is the best of them all.

Nineteen sixty four was Ayler's summit. Later armatures housed some aspects of his vision at the expense of other, rarer forces. His field of fire may have been narrower, but it was certainly deeper, and—17 years after the event—it still shakes the heart like a shock. Plenty of familiar Ayler themes here, all sounding like a Wessex pub gathering standing in for Fate in a Hardy novel.

"Angels" opens to an unbearably tragic, ragged, juddering unison of horns over standing bass strokes and snare rushes. There is little accuracy in any of Ayler's theme statements, which wander off pitch, backfire and howl; detail seems not to interest him, here or during his solos. He has broad, dramatic shape in mind, and will gabble repetitively, albeit with great projection and momentum, until he has blocked in what is necessary as a counterpoise to his grand moments.

He delights in the tumble of pell-mell, the high held yell over hugely pulled bass strokes, the heavy bounce between the extremes of register, the demise of a truculent note into a pleading, the movement of a motif out of focus, either by the use of a flattening speed, an unusual pitch or a grotesque busker's vibrato. An obstacle course—and then some—it is a measure of his spirit that the melodic material not only avoids parody, but actually gains nobility.

"Spirits", Cherry seemingly opening on a different tune and overruled, has Ayler's finest solo, one of those unstoppable "Ghosts, Second Variation" exorcisms, daftly interrupted by the cornettist, and continuing to climb, honk in the bass register, and combine the two extremes in a split-note advance.

Everywhere else, Cherry is marvellous. On "Ghosts" he sounds as if he were taking the thematic material through a series of run-ups without caring for a leap, while on "Spirits" his solo is as vestal and hysterical as a witchhunt.

Some of the most extraordinary music ever devised, and indispensible.

BRIAN CASE

*

New Musical Express (1981) - UK

THE RELEASE of hitherto undocumented work by ‘60s giants underlines how much recent jazz still owes to their pioneering and what a vast wellspring of resources it was. Albert Ayler’s ‘The Hilversum Session’ (Osmosis - Dutch import), a radio date from 1964, retains a blistering impact that makes the time lag meaningless.

It’s the classic Ayler Quartet - the leader on tenor, Don Cherry’s skywriting trumpet as superb foil, Gary Peacock and Sunny Murray in the engine room - working a programme of the saxophonist’s familiar themes. Ayler’s sound is an awesome amalgam of screaming lunges into the extremes of register, exaggerated vibrato lending an edge of cutting poignancy. His compositions are basic as earth, a folkish simplicity imbuing the framework for his incantatory drive.

To pick just two, ‘Ghosts’ and ‘Angels’, are at once frightening and moving, towering statements torn to tragic tatters. A set like this makes a nonsense of this music being ‘difficult’. Ayler demands involvement, almost as if he were dangling his heart before you. Albert forged a crucible of emotion which too many copycats have mistaken for vacuous raging. Hear the original, and marvel.

RICHARD COOK

*

Leidse Courant (7 March, 1981, p.22) - Netherlands

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Click the picture for a readable version.]

Record Reviews

Discography: The Hilversum Session

*

Bells

Down Beat (Vol. 32, No. 20, 23 September, 1965 - p.34) - USA

Albert Ayler

BELLS—ESP Disk 1010: Bells.

Personnel: Albert Ayler, tenor saxophone; Charles Tyler, alto saxophone; Donald Ayler, trumpet; Lewis Worrell, bass; Sonny Murray, percussion.

Rating: no stars

Pharaoh Sanders

PHARAOH—ESP Disk 1003: Seven by Seven; Bethera.

Personnel: Stan Foster, trumpet; Sanders, tenor saxophone: Jane Getz, piano; William Bennett, bass; Marvin Pattillo, drums.

Rating: * * * ½

The Ayler performance was recorded at the concert of avant-garde music held May 1 at New York’s Town Hall under the aegis of Bernard Stollman and ESP Disk, which Stollman owns. Just why it was recorded is difficult to conjecture, for what is preserved on this one-sided LP is perhaps the most formless, incoherent, and quite possibly the most ineptly stated pronunciamento from the outer (and outre) reaches of the “new thing” I have heard.

The first half of the work is a sprawling, turbulent devil’s brew of unrelated sounds, squawks, bleats, cries, whinnyings, etc.—a musical gobbledygook that is almost impossible to describe. It sounds like a henhouse gone berserk.

Ayler surely is capable of wresting a wide variety of effects from his instrument, but music is more than a catalog of effects. The mere airing onstage of a sequence of unrealized emotions through a musical instrument does not in itself amount to the creation of a coherent musical design. Granted the importance in today’s music of the act of creating, still that which has been created through that conscious act must be directed by a musical intelligence and must be fully capable of standing (and being judged) on its own terms—as a finished artifact—aside from the act.

And this is the flaw of the Ayler work; repeated listening reveals no design, no intelligence, no coherence—no art, if you will. (The fact that one can reproduce at will the sequence of sounds that was produced on the stage of Town Hall that evening through the simple expedient of placing this recorded memorial on a turntable does not, of course, amount to anything approaching the existence of a design or musical unity. The unity must be central to the musical experience itself and must be directed by the consciousness of the artists involved.)

The second half of the composition employs a number of simple, folkish motifs to which the participants return from time to time (so there was a plan, at any rate). What bridges these segments, however, is more of the inchoate, feverish disorder that marks the first part; again, no coherence.

Perhaps the high premium these musicians place on the role of intuition in this music can have meaningful results; one can only hope they are right. But it would seem to call for more accomplished and sensitive musicians than were gathered on stage at Town Hall this evening. Either that or they just had a bad night.

The recording is a bit muddy at times; in the ensemble, for example, it is difficult to hear the bass, though this is not a problem in the passages featuring the rhythm section.

What a pleasure it is to turn to the music of the Sanders quintet. It has, among other things, a strong sense of musicality; both pieces, in fact, are quite lyrical in their way. The two performances are ordered, sensitively executed (to the demands of the music), and quite accessible. (True, they are quite a bit more conventional than the free-for-all character of the Ayler piece.)

This was my first exposure to the playing of saxophonist Sanders, and he’s not at all the perfervid iconoclast the writings of LeRoi Jones, among others, had led me to believe. He’s more a modern mainstreamer, if I may use such a term, than anything else, with his strong, sure, muscularly lyrical playing firmly rooted in that of John CoItrane. He has made one of the most wholly successful working syntheses of Coltrane’s mode of playing than anyone I’ve yet heard (with the possible exception of the excellent Booker Ervin); but I would scarcely say, as has Jones, that Sanders’ approach represents a significant extension of Coltrane’s. If anything, Sanders is much more spare and conjunct, much less complicated and rhythmically simpler, than is the current Coltrane.

Sanders’ playing soars with a songlike simplicity that is most attractive, and his tone is very like Coltrane’s in its pain- tinged ardor. He has a pair of beautifully constructed, flowing solos on Seven; toward the end of his first one he employs very effectively a rhythmic figure to which he returns from time to time, imparting a nice sense of continuity to his improvisation.

On Bethera he is much more patently “new thing” in his playing, employing in his solo a sequence of cries and harsh-sounding wails. But they are not gratuitous, being, instead, integral to the mood of the song. Foster enters as from a great distance with a solo that is equally restless and “tortured.” The trumpeter seems quite at home in this music, and his playing, though occasionally tentative and meandering, is generally strong and assertive. The free interplay of the two horns at the end of the piece comes off quite well.

The rhythm section is very good. Miss Getz’ piano is full and complements the playing of the two horns more than adequately; in solo she holds her own. Her right-hand lines are coherent and lyrically spare though not at all dry. Bennett’s bass participates actively, and drummer Pattillo generates an appropriately sprung rhythm.

It’s a most promising group that has much to say and which says it authoritatively and ungrudgingly—and with no polemics either.

One niggling quibble: there seems to have been a bit of print-through on the tape, with the result that one hears a faint pre-echo of the music a split second before it is played on the disc.

(P.W.)

Pete Welding.

*

Jazz Monthly (December 1965 - p.3) - UK

BELLS:

Donald Ayler (tpt); Albert Ayler (ten); Charles Tyler (sax); Lewis Worrell (bs); Sonny Murray (d)

Town Hall, New York City—May 1, 1965

Bells

ESP Disk 1010 (45/3d.)

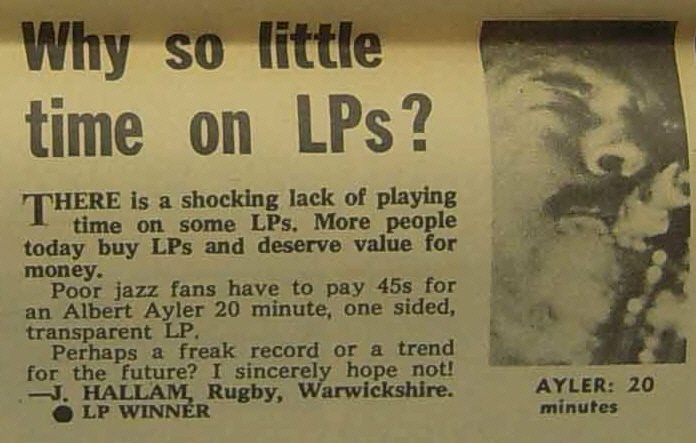

Note:This is a single sided LP.

PERHAPS IT would be best to deal first with the most obvious features of this album—its drawbacks—all apparent before putting the disc on the turn-table. As many will know, for the record is sure to achieve some notoriety, it is a one- sided pressing on colourless transparent material; the second side is taken up by the art-nouveau title design. I’m not against experiments in presentation but it is certainly a lot to expect people to pay a relatively high price for only one side of music, playing time 19 minutes, and this with the added injury of near complete absence of information and no discussion of the unfamiliar music and musicians. The quality of the contents must be very considerable to transcend these barriers.

As it happens Ayler’s music is the most strikingly original to have arisen in the post-Coleman era, indeed he is one of a very few artists who are completely within the new music. Free jazz is slowly confirming its validity by the production of major talents; it is becoming clear that Coleman and Taylor will not remain isolated figures and that there is room beyond. Ayler at 29 is beginning to create his own circle of influence—as can be seen from a chronological study of his recordings—as well as the expected reflex of misunderstanding and scathing attacks, though behind even these the unique atmosphere of the tenorist’s music has clearly left an impression.

The present recording contains Ayler’s section of the New York Town Hall concert that included Bud Powell, Byron Allen and Guiseppi Logan and it is incredible that the other side of this disc was not devoted to performances by the other avant-gardists—instead Logan also has an album to himself. Although there is mention on the sleeve of only one title there appear to be two distinct compositions—though a “two part work” is possible—the first, fast and tumultuous, lasting some 5½ minutes and a more varied piece which I assume is Bells itself. It is probably the most internally consistent example of the artist’s work on record, for the other musicians have obviously steeped themselves in his individual concept. Indeed Tyler is so close to his mentor that one must rely on an eye-witness to inform us that he is playing alto—despite this dependency the powerful solo preceding the trumpet on the second piece indicates great potential. Don Ayler is the most compatible trumpeter his brother has recorded with, though Don Cherry’s partnership also proved fruitful, and Lewis Worrell is another wonderful bassist and one who will listen. Murray, a frequent colleague, is completely adapted to the independent rhythm of Ayler’s solo style and provides the jazz equivalent of the noise elements in this neo-gothic world.

For Ayler himself one can hardly summarise the nature of his unique style in the course of a review. He is a gifted fantasist, his incredibly powerful and coarse tone shaping a soundscape of gryphons and gargoyles, a weird contorted landscape broken by passages of black comedy. Structural development does not play much part in this essentially static style, yet the emotive power and perverse humour combine with technical consistency to produce a unified art. His themes are equally part of the expression, strange often brilliant fusions of half-remembered folk-tunes or common martial airs that underline the child-like aspect of his approach and call forth a nostalgic response to complicate the trenchant darkness. In the second piece suggestions of The Bells of St. Clemens, Frere Jacques etc. combine with the basic military call to arms—played at an edge of chaos that takes the brass band parody into a new dimension. Technically he has continued the constant expansion of the saxophone’s range to hitherto unheard extremes—one wonder on hearing the dynamic and timbral possibilities now available (note the trumpet-like passages here) if soon the reed instruments will satisfactorily replace all other horns in jazz usage—not a purely speculative idea as a glance at jazz history will bear out.

All in all this writer finds it difficult to offer a final recommendation; short playing time, irresponsible presentation, and dubious sound quality, or strikingly original musical thought capable of immense rewards if given the opportunity—the reader must decide for himself.

TERRY MARTIN

*

Melody Maker (4 December,1965, p.20) - UK

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jazz Hot (1966) - France

BELLS

Albert Ayler (ts), Don Ayler (tp), Charles Tyler (as), Lewis Worrell et Gary Peacock (b), Sonny Murray (dms).

Bells.

Mai 1965, Town Hall, New York City.

ESP 1010.

“Bells”, comme tout le monde l’a bien compris, c’est vraiment le manifeste de la Nouvelle Musique. C’est à partir de ce disque que lui, Albert Ayler, et tous les autres sont devenus ce qu’il sont; soit en s’y opposant, soit en se croyant enfin libres d’aller jusqu’au bout d’eux-mêmes.

Albert est sans doute le premier musicien depuis Bird à ne pas se soucier sincèrement de son art, ou mieux, de son expression. Il sait, parce qu’il les a expérimentés, que les seuls vrais sommets de l’intelligence et de la perception sont formés (obtenus) par la multiplication des accidents-événements et que l’unicité est devenue un centre trop inutile pour ne pas être condamnée à se balancer stérilement d’avant en arrière de la création. Le ventre de la phrase, le coeur de toutes les syntaxes est en fait (médiocre soleil) une donnée trop facilement réductible à la notion matricielle de vecteur; quand ces vecteurs sont déclarés informels, il en profite pour se détourner et regarde hypocritement vers la vie (les marches militaires), le rêve peut alors se contenter d’être lui-même. Pendant les époques limites, le seul point de fuite, la seule planche de salut, se trouvent du côté de la brûlante succession des climats. Mais une succession en boucle: recommencer le déjà énoncé, s’engloutir dans son point de départ, réamorcer l’acte qui s’achève, s’enrouler autour de son propre projet, c’est l’arme unique que nous possédions pour nous opposer au silence (on parle trop du silence); ce silence où nous pensions nous enfoncer, épuisés, battus par l’inhumaine et fulgurante rapidité du défilé des antinomies en liberté. La cercle: règle d’action des positifs et des négatifs organisés en chaine...

La structuration des matérieux est-elle donc si vaine quand elle se fait pour elle-même? La musique d’Albert est une réponse impérative et injuste. Un beau matin, il se retrouvera sans nécessités, debout au milieu de son magnifique espace comblé de fleurs mortelles qu’il n’aura pas voulu (désiré) engendrer; il feindra la surprise, jouera la carte de la maturité; il sera alors lui aussi bel et bien confronté avec l’inepte futilité de toute musique... Il croira au personnage qu’il sera devenu at au vocabulaire qui se mettra tout à coup à sa disposition, c’est ce dernier coup qui lui sera fatal... Ce sont les professionnels du son qui recherchent les grands dialogues à l’intérieur de leurs oeuvres, Albert n’aura qu’entrepris la quête du matériel sans qualité (sans jamais chercher à réussir, cela aurait déjà été une forme, son manque de lucidité le protège: il voit clair).

“Découverte”: ne plus faire de fausses notes mais des mauvaises notes.

Tout au long des cultures, à intervalles réguliers, apparaissent de ces sortes d’antiprogressistes qui font toucher le but; Albert doit se savoir condamné: il nous laisse un récit déjà presque complet et sans l’ombre d’une faiblesse ou d’un doute. La ligne — ou le son — se dissocie, s’arrache de la forme, de la couleur, du dessin, elle se précipite vers son propre jeu (d’implication sociales); et c’est par dessus ou au creux de ces énormes entrelacs qu’il capture ces minuscules unités de lumière qu’il avait laissé s’échapper.

La force sans muscle de sa musique, quand elle se déploie, appelle la fragilité de son destin. La MUSIQUE qu’il émet par l’intermédiaire de son instrument est la seule à être plus férocement constante que lui-même. Le grotesque dont parlent ceux qui “écoutent” Albert représente presque trop parfaitement la manière dont ils en sont environnés, pris au piège. Après lui, les nouvelles inventions seront difficiles car le sexe de sa musique appartient à ceux qui pourront lui répondre malgré tout sans montrer trop de panique. Cette course aux atmosphères marque l’affaiblissement irrémédiable de toute “perfection”. Cependant il y a encore Marion Brown...

Alain Corneau

Record Reviews

Discography: Bells

*

Spirits Rejoice

Down Beat (Vol. 33, No. 18, September 1966, p. 28) - USA

Albert Ayler

SPIRITS REJOICE—ESP 1020: Spirits Rejoice; Holy Family; D.C.; Angels; Prophet.

Personnel: Don Ayler, trumpet; Charles Tyler, alto saxophone; Albert Ayler, tenor saxophone; Call Cobbs, harpsichord; Henry Grimes, Gary Peacock, basses; Sonny Murray, drums.

Rating: * * * ½

Albert Ayler is one of the most original jazz tenor saxophonists and probably will become one of the most influential. He has already marked the styles of a number of young musicians.

He is, however, far from being a perfect musician. On this album the virtues and shortcomings of his approach are clearly illustrated. He hurls himself violently into almost everything he plays, seldom improvising with restraint for very long. His work is often extremely violent. Speed is a very important element of his playing. He sometimes plays so fast that the notes in his phrases nearly seem to lose their identities; it’s almost as if these extremely complex lines were not composed of individual notes but were ascending and descending unbroken ribbons of sounds.

When playing this way, the tenorist does not have much time to think; consequently his extremely agitated playing does not have melodic substance. (Some of the runs and phrases he chooses to play lie under his fingers in such a way that they are relatively easy to play swiftly. They are sometimes rather trivial melodically.)

His playing derives its interest from its speed and from its author’s use of varied textures and colors and freak effects, i.e., rasped and honked tones and high notes that are above the normal upper register of the tenor saxophone. When he plays fast, his tone is extremely dry and cuts like a knife.

His fast playing is explosive and powerful, but during some of these solos, it sometimes becomes boring, the result of several factors. For one thing, he does not build to a fever pitch; he starts at one and stays there. His fast work then lacks variety; it is pretty much on one level of intensity. It also does not have particularly good continuity, for he does not seem concerned, when playing fast, with making a smooth transition from one phrase to another.

It is interesting to contrast Albert Ayler’s fast playing with John Coltrane’s sheets of sound, which preceded it. Coltrane’s sheets are much richer in distinctive melodic and harmonic ideas.

Tenorist Ayler’s fast solos here are fairly short, but they have dull moments as well as arresting ones. In fact, his work on the Spiritual Unity LP (ESP 1002) is, I think; generally more imaginative.

I should mention that he has demonstrated, when playing in a relatively calm manner (particularly on Spirits, ESP 1002), that he can improvise interesting melodic lines, full of fresh (in their context) intervals.

On the other hand, his work is sometimes extremely romantic. From time to time he employs a tone that is so syrupy and plays so shakily that it goes beyond parodying the “sweet” saxophone style.

It’s a jarring experience to hear him play romantically. Sometimes his slow work is invested with a quality that might be called insane, or at least eerie; often it’s quite moving.

I react differently every time I hear his gushing Angels work, usually finding it humorous. Others may think it poignant. It’s sort of like watching an intense but clumsy suitor. You don’t know whether to laugh or sympathize.

Donald Ayler attempts to emulate his brother’s approach, but with less satisfactory results.

Trumpeters can profitably pick up some things from Albert, but it would appear to be a mistake, in most cases, for them to base their styles entirely on his. Many of his pet devices are extremely difficult to approximate on trumpet. Donald, for example, doesn’t even attempt to scream in the upper register, like Albert. He would need an iron lip to do so. He seems to take the easy way out, playing a lot of notes to little purpose. His work has intensity but little of the textural richness of Albert’s.

All of the compositions are credited to Albert Ayler. He is an intriguing writer. His pieces sometimes have an old-fashioned quality and are composed of odd combinations of elements.

Spirits Rejoice is reminiscent, at some points, of martial and processional music. Some of the compositions would not be out of place in the sound track of a movie about royalty in 18th-century Europe. It even has a snatch that’s reminiscent of La Marseillaise.

Angels, a slow, sentimental composition, derives its interest from the weird coupling of harpsichord and tenor saxophone (especially the way Ayler plays it) with discreet rhythm-section backing. It’s a humorous selection, sounding like a put-on in various spots, but the humor is almost certainly unintentional.

The veteran Cobbs, who played with Johnny Hodges in the ’50s, turns in some fleet, exquisite harpsichord work on Angels.

Family, a simple, trivial piece, sounds a little like hoedown music.

There are better Ayler albums available, but anything he does now is worth having.

(H.P.)

(Harvey Pekar)

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 135, October 1966, p.55) - France

[Combined review]

*

Jazz Hot (1966 ?) - France

[Combined review]

*

Jazz Monthly (Vol. 12, No. 11, January 1967 - p.14) - UK

SPIRITS REJOICE:

Don Ayler (tpt); Charlie Tyler (alt); Albert Ayler (ten); Henry Grimes, Gary Peacock (bs); Sonny Murray (d)

Judson Hall, New York City—September 1965

Spirits rejoice :: Holy family :: D.C. :: Angels-1 :: Prophet

1-Call Cobbs (harpsichord) added

ESP-Disk 1020

SEVERAL ALBERT AYLER records have been reviewed in Jazz Monthly already, all but the most incurious readers will have heard at least one of them and have some idea of what his music is like. We are well on the way, I believe, to his recognition as an outstanding figure in post-Coleman free jazz. This new disc finds him using a similar instrumentation to the single-sided ESP 1010 discussed here in December, 1965. In another publication I’ve already suggested Ayler has found a whole range of new effects within his tenor, and that such discoveries are part of the jazz tradition. An obvious parallel is the growl brass playing Ellington featured from the ‘twenties onwards. However, Bubber Miley—to take the obvious example—had something more than an amazing range of new brass effects: he had a personal, surprisingly delicate, brand of melodic invention. Can anything similar be said of Albert Ayler? This is not the time to restate the thesis on free jazz which I outlined when writing of David Mack’s twelve-tone LP (Jazz Monthly, October, 1965) and expanded for our avant-garde issue last June, but one point must be repeated. Whereas Cecil Taylor’s atonality represents the continued influence of European tradition on jazz, George Russell’s lydian ideas an attempt at a theoretical alternative, and Ornette Coleman a bypassing of that whole complex, the work of Ayler, Sun Ra and others marks an attempted rejection of jazz’s ‘European experience’. This is why, whether it be a conscious decision or not, Ayler, trying to re-establish the pre-harmonic ‘innocence’ of American Negro music, uses not merely simple material but the most basic musical archetypes imaginable. For instance, bugle-type calls are one of the most elementary kinds of construction and, so far as instruments are concerned, probably one of the oldest. So, Spirits rejoice is a kind of wild heterophonic fantasy on such motifs. It is mainly a collective improvisation (sounding one step beyond Mingus’s more abandoned moments) in which the seemingly caricatured ‘military’ phrases return periodically. Each horn has a period out front, but even then basses and percussion are busy with their disjunct yet complementary patterns. Perhaps because the concern is with ‘sounds’ rather than with ‘notes’, separate phrases mean little in comparison with the overall effect of whole passages. Thus the “skittering around energetically” of which I complained last June adds up to more than I was then able to hear. A good example is the extraordinary texture achieved twice by the horns collectively in high register towards the end of Prophet. We are far here from the “mere hedonistic play with sound” which, as I said last year, is a danger for the new jazz. That, presumably, is an answer to the question asked about Ayler above. And the roots of this music in the ‘non-European’ aspects of earlier jazz are becoming clearer. For example, the duet between Don Ayler and Murray at the beginning of D.C. is, again, one step beyond, say, Lee Morgan riding the storm of Blakey’s drumming. There are other advances, for instance on Coltrane’s use of two basses. With Coltrane they still marked time, in however complicated a fashion, didn’t alter speed and didn’t play lines really independent of the horn(s). Here they do. There is greater—and significant—freedom between basses and percussion, both among themselves and in relation to the horns. And hear the bass duet on Prophet.

As you’ll have gathered, this is a good one. I could write as much again about it but suggest you find out for yourselves. If you’ve the equipment, the stereo pressing is preferable as it helpfully separates the two basses and two saxes.

MAX HARRISON

*

Guerrilla (Vol. 1, No. 1, January 1967 - pp. 24-25) - USA (Detroit) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jazzwereld (January, 1967 - p.25) - Netherlands

„Spirits Rejoice”

Spirits Rejoice (1) - Holy Family (1) - D.C. (1) - Angels (2) - Prophet (1).

Albert Ayler (ts), Don Ayler (tp-1), Charles Tyler (as-1), Call Cobbs (clavecimbel-2), Henry Grimes (b), Gary Peacock (b), Sonny Murray (d).

New York, september 1965.

ESP 1020 1 22.50

* * * *

Een van de manieren om de Ayler van ‘Ghosts’ en ‘Spiritual Unity’ te beluisteren is als naar een tenorist die is verder gegaan met ‘Chasin’ the Trane’ op het punt waar Coltrane er mee ophield: grommend, piepend en met een opmerkelijk vibrato blaast Ayler op die LP’s duidelijk een aantal variaties op een thema waarvan de ruwe melodische contouren in elk nieuw chorus zijn terug te vinden. Op ‘Bells’ en ‘Spirits Rejoice’ is hetzelfde procédé opnieuw te horen, maar hier in een sterk gecomprimeerde vorm. De thema’s waarover Ayler en de zijnen improviseren zijn nauwelijks meer dan uit een paar noten bestaande motiefjes, signalen uit een denkbeeldige kazerne, die van de musici het uiterste vergen om er nog boeiende aspecten aan te ontdekken. Tyler faalt daar dan ook nogal eens in, maar de Aylers en de beide bassisten lukt het wonderwel. Van een melodisch verloop in de gebruikelijke zin is bij deze werkwijze natuurlijk geen sprake meer. Waar dan wel sprake van is kan misschien verheldert worden met behulp van een uitspraak van Don Ayler: „Neem bijvoorbeeld twee willekeurige noten. Normaal speel je de ene, dan de andere. Maar wij hebben de neiging beide noten tegelijk te spelen, èn alles wat er tussen is.” En de steeds herhaalde pogingen om dat waar te maken, het thema bestond immers uit maar een paar noten, vormen samen een solo. Een spel dus met contrapuntische mogelijkheden (vgl. ook Trane’s dubbeltonen-toer) op instrumenten die daar van huis uit eigenlijk niet voor bestemd waren. Solo’s waarin dit spel vindingrijk en met stijgende intensiteit wordt beoefend lopen dan vaak heel logisch uit op een enthousiast collectief vrij contrapunt (Prophet!). Een verrassende variant op deze hele aanpak biedt „D.C.” dat een thema in ‘spiraalvorm’ heeft, het signaal wordt steeds vlugger gespeeld terwijl het ook steeds korter wordt zodat tenslotte alleen het staartje overblijft. Dat spiraalachtige te handhaven blijkt dan ook nog een van de opdrachten aan de solisten te zijn. (Misschien is dat wel te veel de projectie van mijn eigen strompelend oor in de muziek. Maar het geeft in ieder geval degenen die Ayler c.s. vormloosheid verwijten stof tot nadenken.)

Ook in zijn voorkeur voor poparterig materiaal gaat Ayler nu veel consequenter te werk dan op zijn platendebuut (‘My name is Albert Ayler’ beschouw ik als een valse start die niet meetelt). Kon men bij ‘Ghosts’ voornamelijk bij het breng- mij-terug-naar-die-outransvaal-motief een grijns van verstandhouding wisselen met de medeluisteraar, bij ‘Spirits Rejoice’ is het wat dit betreft een waar feest der herkenning. Vooral bij het titelstuk, dat begint met een collage van vijf min of meer bekende voortbrengselen der populaire toonkunst (titels onthouden heb ik nooit gekund): een gedragen Aznavour-original (volgens een kenner), een ‘jagerstetteretet’, een als koraal behandeld brok ‘Marseillaise’, een gaaf stuk smartlap, nog eens de marseillaise waarna iets in de geest van ‘last post’ of zo. „Holy Family” is zelfs uitsluitend een door Ayler vrijwel straight geblazen twist (again); de andere heren verzorgen intussen een keurig orgelpunt. Ook het thema van „Angels” komt mij vaag bekend voor (genre: Chapel in the moonlight); een langzaam en onbeschaamd sentimenteel stuk muziek dat er onder Ayler’s handen wezen mag. Het clavecimbal fleurt de lang aangehouden tonen van de tenor op met een vriendelijk metalig getinkel; Call Cobbs roesjt graag met de duim langs het klavier en doet daarnaast dingen die hem in mijn oren tot een vrolijke oude swinger bestempelen.

Wie overigens mocht denken dat het bij het aan bod komen van deze kant van Ayler alléén maar lachen geblazen is heeft het mis. Zo kinderachtig en overzichtelijk liggen de zaken echt niet. Wat Ayler met andermans werk doet lijkt op wat Strawinsky in zijn Pulcinella met Pergolesi deed. Ik mag het graag horen.

Martin Schouten

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 222, May 1974) - France

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And this turned up on ebay - no information as to the source:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[2020: Thanks to Robin Storey Dunn for the better copy.

2024: Found the original magazine at the Internet Archive. This is from

Hit Parader (August 1977 - p.19) - USA]

Record Reviews

Discography: Spirits Rejoice

*

Sonny’s Time Now

Jazz Monthly (May, 1968 - p.21) - UK

SONNY’S TIME NOW:

Don Cherry (tpt); Albert Ayler (ten); Henry Grimes, Louis Worrell (bs); Sonny Murray (d); LeRoi Jones (ranting-1)

Virtue :: Black art-1 :: Justice

Jihad 663*

*Obtainable from: Jihad Productions, Box 663, Newark, New Jersey, U.S.A. @ 5 dollars.

THERE is little a mere pianist can hope to add to Jack Cooke’s admirably lucid and detailed account of Murray’s work which appeared in “Jazz Monthly” for November, 1967. But as the above disc was not to hand when he was preparing that essay readers may like a few comments now. Its only disadvantage is “Black art”, which features LeRoi Jones yelling one of his ‘poems’. Most of this sounds like a prurient schoolboy trying desperately hard to be shocking, except that at the words “airplane poems” he imitates the noise of an aeroplane, then of a machine-gun, like a child not yet old enough for school. In contrast to such inspirations there are some nasty racialist moments, of which “dagger poems in the slimy bellys of the owner Jews” is representative. Whatever extenuating circumstances there are, I regret fine musicians such as Cherry and Ayler associating themselves with this, the more so as everyone plays so well on the other tracks. “Justice” and “Virtue” are heterophonic performances without chorus divisions or bar-lines and are sustained by the thick, dark, continuous textures of Murray’s drums and the basses. Quite often one or other of the two horns will drop out, and Cherry has a particularly good, brooding passage on “Virtue”. The intensity with which horns, basses and drums react with each other makes one hesitate, though, to describe any given part as ‘solo’ or ‘accompaniment’. Certainly the most striking moments come when all five players are involved, a good instance being the quiet, almost trapt, vehemence of the long collective improvisation in “Virtue” which precedes the passage for drums and basses alone. Cherry, Ayler and Murray, indeed; are excellent foils to each other, as “New York Eye and Ear Control” showed (ESP 1016, reviewed in these pages last October).

MAX HARRISON

*

[This review provoked a long-running controversy in Jazz Monthly. Since the ‘discussion’ was not Ayler-specific, I’ve placed the relevant items on a separate page:

Pages from Jazz Monthly relating to Sonny’s Time Now

The various reviews, articles and letters do give a flavour of how ‘free jazz’ was viewed at the time, in Britain at least. I should also point out that among the British jazz magazines, Jazz Monthly was the most sympathetic to the avant-garde. One of the items, which bears repeating here, is the following letter from Max Harrison.]

Jazz Monthly (No. 169, March 1969, p. 31) - UK

Cherry/Ayler/Murray/Jones/Burke/Berk

THOSE readers who were as amused by Patrick Burke’s damp little squib in the February issue as by his more strenuous efforts last July might be still further diverted by the comments on that Sonny’s Time Now Jihad LP which follow. They are by a close friend of Don Cherry’s who prefers, alas, to remain anonymous. However, if I say he occasionally writes for this magazine sharper readers may be able to put two and two together without making five out of it.

“As you said in your review, there is some fine jazz on the album. This is a great pity in some ways, for reasons that will become clear below. I’ve had the Jihad disc for what seems like a long time and my feelings about the LeRoi Jones ‘poem’ are similar to yours. One day when Don Cherry was at my place I asked him about the session because I couldn’t understand how in hell he or Albert Ayler got to be associated with that stuff. Don’s only positive remark was, ‘Wow, Sonny’s got a record out!’ The rest was obviously hurting him. It seems there was a wild party—probably Xmas or New Year—at which pretty well everyone got drunk. LeRoi Jones took advantage of the situation, got a cab and shuffled horn men over the east side to the Black Arts Theatre or some place like that. The rhythm men were, I gather, awaiting their arrival, much to Don’s and Albert’s surprise. They were assured that this was a private session, but couldn’t help noticing the set-up of recording gear. . . . it was some kind of dunky studio. All this appears to have been strictly LeRoi Jones’s deal for the Black Arts Rep. Don Cherry has no clear recollection of what, if anything was played at the session, by which I mean he didn’t recognise the material when the disc was played. About all he could say was that it sounded pretty definitely that he was on that session, and he didn’t dig the idea one little bit.”

Unfortunately, it is hard completely to accept all this because if Ayler and Cherry had been so drunk as to have no real memory of the session they could not have played so well. Also, one would like positive comments from Ayler or someone as close to him as my informant is to Cherry. But it is obvious I owe both musicians an apology for assuming they did go along with Jones’s ranting—although this was surely a natural conclusion to draw under the circumstances. What is also obvious is that Patrick Burke owes everybody an apology for asserting “Roi is speaking for them/of them”.

That gentleman is equally wrong to suggest I devoted five columns to defending myself on this matter. What in fact happened was I used his first ridiculous letter as a peg upon which to hang my opinions on several aspects of ‘sixties jazz. Those who read New Thing Notes properly will know this already, of course, but perhaps I should spell out that the exaggerated schoolboy humour of my remarks about him was deliberate, being intended as an ironic comment on the level of his arguments. It seems I should have remembered the advice Stanley Dance gave me about 12 years ago: “Never be sarcastic in a jazz magazine—at least half the readers will take it at face value. And as for irony. . . .” Still to judge from the total evasion of his second ridiculous letter, I did at least get Mr. Burke’s range.

MAX HARRISON, London, W.12.

Record Reviews

Discography: Sonny’s Time Now

*

At Slug’s Saloon

The Wire (No. 3, March 1983) - UK

[Combined review]

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 753, October 2022) - France

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Record Reviews

Discography: At Slug’s Saloon

*

Lorrach/Paris 1966 (aka Jesus)

La Stampa (9 January, 1982, p. 7) - Italy

|

|

|

|

|

|